A Year of Worldschooling: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Homeschooling your kids while traveling abroad long-term is sometimes referred to as worldschooling. Whether that sounds like a great idea or a complete disaster, prepare to have our experience bust your preconceptions.

When we told our friends we were pulling our kids out of school for a year to travel South America, we generally received two opposing reactions. The first: What are you crazy? The boys could fall behind! Homeschooling on the road would be difficult, they worried, if not overwhelming.

Then there were those that thought what we were doing was brilliant. They will learn so much more than sitting in a classroom reading a textbook.

After a full year of experience, I can report that in each opposing reaction there is a kernel of truth.

Table of Contents

- Falling Behind and Other Worst Fears

- They Already Knew The Material

- They Turned Out Fine? But How?

- Homeschooling Is Not for Everyone

- An Un-schoolers’ Paradise

- Did the Good Outweigh the Bad?

Falling Behind and Other Worst Fears

Let’s start with the good news. Nobody got held back a grade.

The year we traveled, our oldest two would have been in third grade and kindergarten. Our youngest boy would have just started preschool.

In recent weeks, we attended a slew of parent-teacher conferences. Their teachers put any lingering anxiety to rest. Our kids did well on their standardized tests and were killing it in the classroom. We were even surprised to learn that both of the older boys are on track to enter the gifted and talented programs. Their teachers spoke of the boys in glowing terms and noted that they already seemed to know the material.

We praised Finley for doing so well, but added, “How come you don’t behave as well at home as you do in school?”

He retorted, “School is where I belong!”

They Already Knew The Material

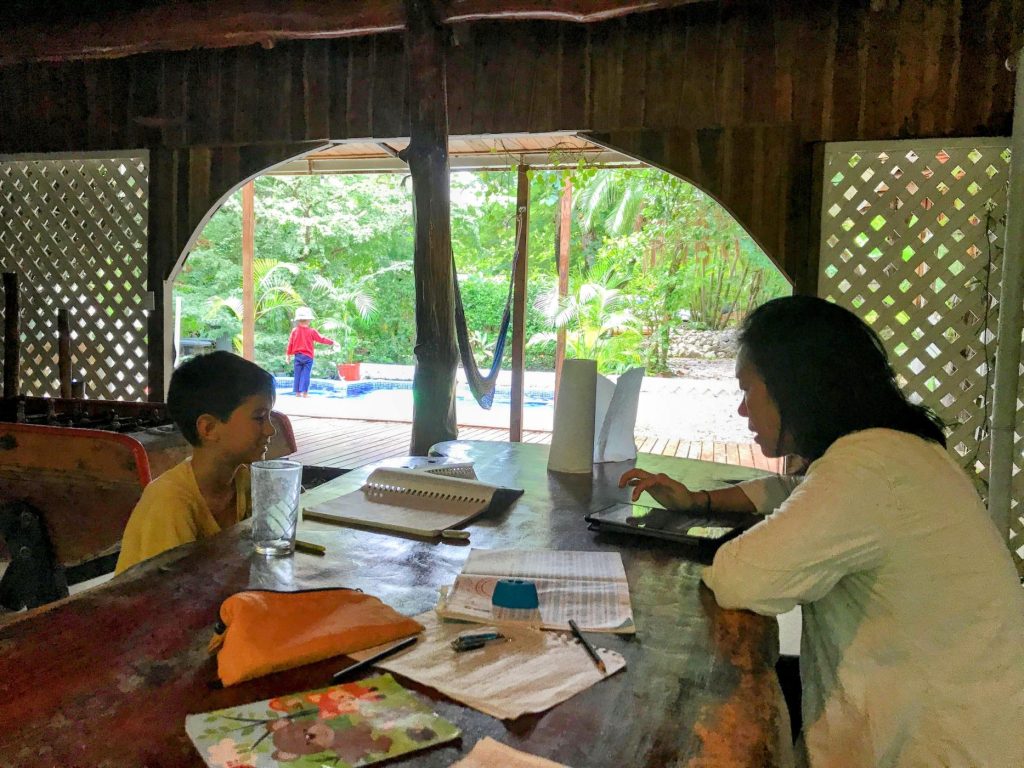

It’s no accident that they are already familiar with this year’s material. Both Liuan and I are the proactive sort. When faced with the possibility of falling behind or failing, we double down. In other words, you can’t fall behind if you’re working to get ahead.

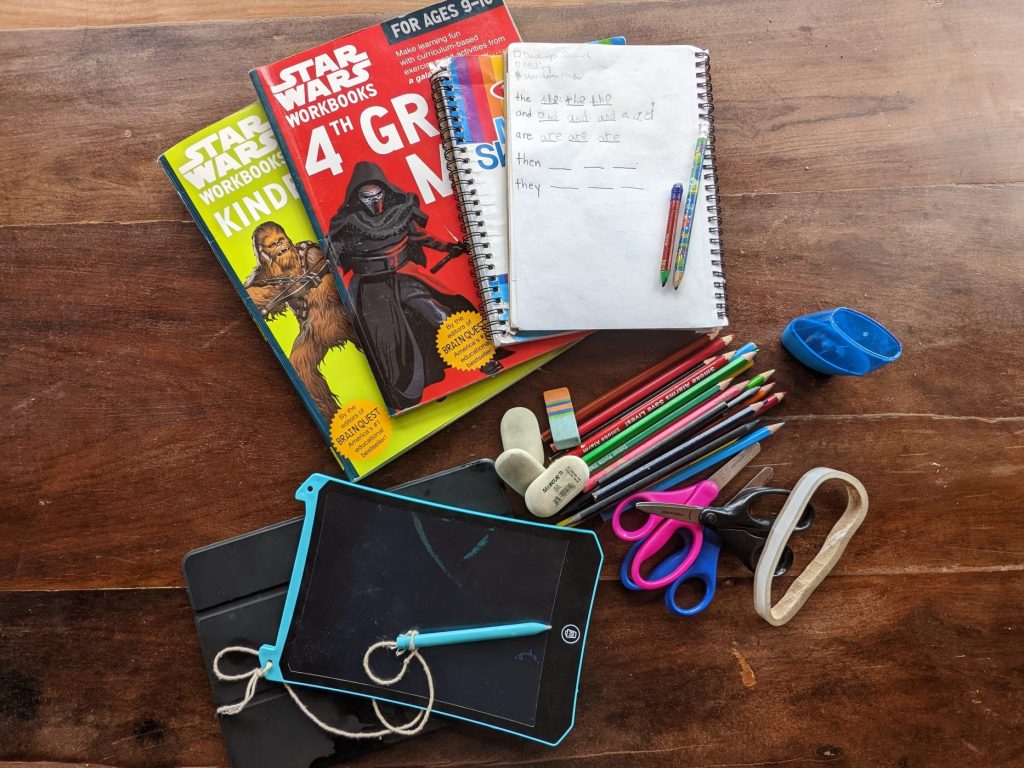

Before we set out, Liuan gathered a set of basic supplies. Each child got a Star Wars-themed math workbook. When they finished their grade level, Liuan got her mom to bring workbooks for the following level when she visited us in Brazil. We set their Khan Academy profiles ahead as well. Was reading and memorizing sight words a first grade thing? Then we drilled Finley on sight words. We made Oliver (the third-grader) write essays and narratives using past tense Spanish.

Liuan and I debated the merits of this approach. I wondered if they might like their school work more if it were at their level. Liuan thought they were ready for the next level. She also felt they would be more confident if they were a step or two ahead of their peers. I’ll let the reader decide for themselves who was right.

Most work was done on iPads and Laptops to keep our packs light.

They Turned Out Fine? But How?

So far, what I’ve shared probably lends itself to an uncomplicated picture of academic success stemming from confident planning and diligent study. I’ll have you know that the actual experience of it felt like a raging dumpster fire, with our kids’ flagging motivation and our dreams of a highly “enriched” education serving as fuel.

Sure, there were some bright spots. Oliver and I programmed a Scratch game to practice multiplication tables. Then, there was the week I watched Finley make serious progress on his sight words.

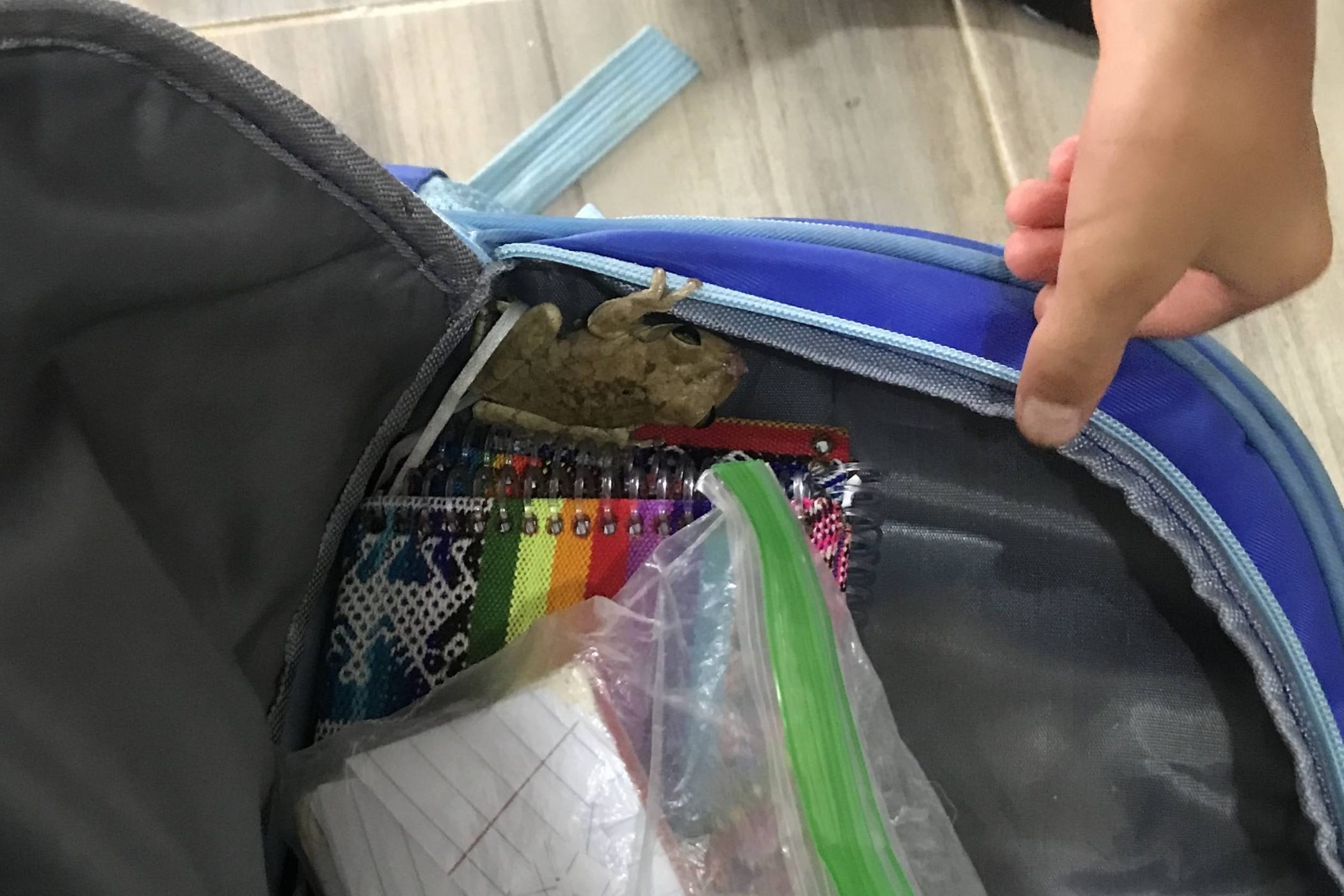

But we should have predicted what we were up against on the first day of “class.” Not twenty minutes into our first session, a marmoset entered our cabin, pooped on the floor, made a big commotion, and upended any semblance of an orderly learning environment.

Our original goal was to set aside two hours a day, five days a week, for homeschooling. That might not sound like much, but we reasoned that much of formal school time is spent on non-educational tasks—roll calls, announcements, standing in line, safety drills, discipline, and accommodating the short attention spans of grade schoolers.

In reality, it was rare that we spent even half that much time on school work. Sometimes we managed two hours in a whole week. Often, we skipped weeks altogether.

School work was the very last thing they wanted to do. Which, of course, meant it was no fun for the parents either. And can you blame us? Just outside our door, a burbling river or bustling street invited us to romp and explore.

Homeschooling Is Not for Everyone

Before we left, we thought we had a chance at really enjoying homeschooling. Liuan and I are academically wide-ranging and curious. Our children are bright and ask good questions. We love getting into discussions with them about big ideas—culture, ecology, physics, language, money, where babies come from, you name it.

But much of what we think of as “school” are the rote skills-based stuff that is measured by filling bubbles with pencil lead. As I taught my son—and retaught myself—long division, I shook my head in disgust. Why would anyone but a calculator programmer need to learn this? And while we’re at it, why are they still teaching cursive? Neither parent, we realized, was skilled at motivating our kids to perfect those skills, even when we managed to see some of them as beneficial in the long run.

I read books on un-schooling. It’s a philosophy of education that prioritizes a child’s curiosity over progress milestones or standardized tests. The books I read encouraged parents to lean in to what the child is obsessed with, trusting that they would gain all the necessary skills in due time. If true, then I wouldn’t have to feel so guilty.

In defense of unschooling, the way I learn things as an adult is precisely how un-schoolers urge parents to teach their kids. I don’t try to cram eight subjects into my brain at once. I learn about one thing at a time as the interest strikes me. And yet… if we want public schooling to remain an option, what are the chances my child will naturally become obsessed with multiplication tables?

Oddly, though, our kids like public school (read about it in their own words). Our kids loved traveling, but they also longed to learn alongside their peers. They derive motivation from the comradery and competition that other children provide.

Friends and acquaintances that have chosen the homeschooling or unschooling track might be horrified to learn that putting our kids back in public school was a big factor in our decision to end our travels after a year. But that’s just us.

An Un-schoolers’ Paradise

Even though we unhappily and inconsistently slogged through reading, writing and arithmetic, we came out the other side better than fine, as you already learned.

But what about the unstructured, non-academic part—the culture, language, natural sciences, and lessons in adaptability that travel is supposed to provide? After all, we didn’t take our kids on a year-long, continental journey just to pore over textbooks.

The kids were indeed soaking up a world-class education. Though it could be hard to detect when disguised as discovery rather than memorization. What did you learn? We didn’t learn anything. was the common refrain. Yet somehow, now they know all these things that I didn’t even know at 20 years old.

They experienced farm animals and food production at the source and witnessed merchants hawking products on the street. They saw receding glaciers in Patagonia and disappearing rainforest in the Amazon. Their bodies became resilient and adept at climbing over boulders and enduring long hikes over rough terrain.

We all learned something about chicken sex.

Though they didn’t come away as fluent in Spanish as we had hoped, they experienced the language in its native context and even got over their self-consciousness and used it on occasion.

We are still unpacking all that happened over the last year. We find ourselves continuing to apply our experiences to new contexts.

Did the Good Outweigh the Bad?

If you are dreaming of embarking on a similar trip with your young ones, you are likely reading this to weigh the pros and cons of taking your kids out of school. And I can say, in our case, we would do it again. One hundred percent. Warts and all.

Our kids reentered the “system” with ease. But even if they had struggled at first, it still would have been worth it. The lessons they took away from traveling South America will surely leave a more lasting impression than long division.

Whether or not your kids have similar outcomes or challenges depends on a variety of personal traits. Though the book work was unpleasant, we kept at it. Sometimes we wasted a lot of time shedding and drying tears. Other times I resorted to cheap fear tactics—reminding them that all their friends were in school seven hours a day and getting way ahead. (Worldschooling parents take note: that worked). What we did wasn’t perfect, but it was enough.

Of course, if you’re unconcerned about success within the formal school system, I probably don’t need to convince you that making the wide world your classroom will be a major win for the development of your child’s curiosity. Nevertheless, even if you can’t bring yourself to cast off conventional academics, consider this one unvarnished story as evidence that you’ll do just fine. Don’t let this particular fear hold you back.

Just one of the many realities of worldschooling.