How We Nearly Failed to Extend Our Tourist Visa in Brazil

The Rules: Extending a Tourist Visit in Brazil

The law, as written, is lenient. Tourists from the United States are allowed to enter Brazil for up to ninety days. No visa necessary. For the typical tourist, that means you can go to Brazil, spend many times the typical vacation allowance, and leave with nothing more than a stamped passport.

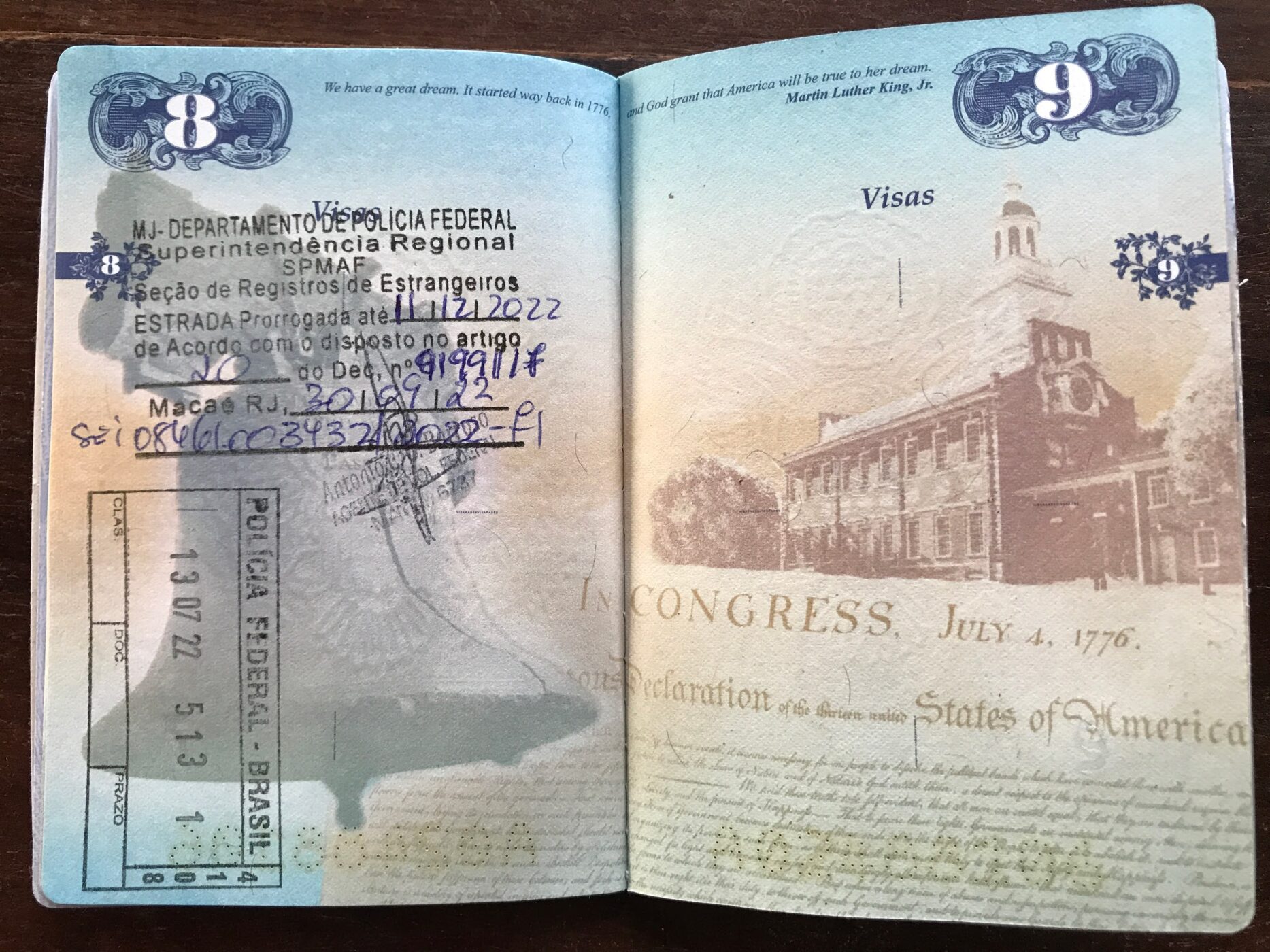

If three months is not enough, you can stay another three months. This does require a bit more process, but in theory, it is still quite reasonable. You fill out a simple form, pay a $20 fee, and then report to a federal police station where they punch your passport. The stamp says when you need to get out, for real.

“It’s just a formality,” said Bart, the founder and director of Eco Caminhos — a permaculture farm we are volunteering for two months.

He continued with some helpful advice. “Go to Macaé, the people are nicer there than in Rio. The key is to be respectful and avoid getting frustrated, whatever happens.”

“Is Macaé close?” I asked.

“Nothing is close,” Bart replied.

This is a story about how “easy on paper” can snowball into a three ring clown circus in real life.

Before I Continue

I’ve had to reflect on why I’m telling this story.

This is certainly not a how-to. I’m not sure what this story has to teach other travelers, except to be prepared for nothing to go right. But as a specific how-to, I’d have to title it “How to Extend Your Stay in Brazil as a Family of Five Living in a Remote Mountain Eco Farm Outside of Nova Friburgo When 30 Hours of Rain Screw Over Your Best Laid Plans.” That’s hardly going to snag organic search clicks.

I’m also hesitant to paint Brazil as some backwater banana republic. Bart, our host at the farm, advised us that if we ever decided to move here, we can’t always complain about the downsides. “If you’re going to gripe about a place you might as well go home.”

The best answer I can give for why I’m taking the time to write this story is because it’s absurd. The absurdity makes it a fun story to tell. It was a straightforward task. Yet it managed to snowball into a ten day saga of false steps, bad options, bad luck, and high-stakes cajoling of Brazilian officials that had nothing to gain by helping us.

That said, this story is an exception. It’s not representative of our nearly four months of travel in Brazil.

No Worries

Most of our days are filled with verdant mountain vistas, trips to the grocery store, sun, rain, dirt, and amicable run-ins with native Brazilians, who always try to be as helpful as they can. In other words, just another variety of typical daily life.

The pleasant days outnumber the outrageous days twenty to one. But the outrageous days make better stories.

The point is, I’m wary of giving those who haven’t yet set foot in Brazil another reason to worry. If you ever have the privilege to travel to this amazing country you’ll see for yourself how little you need to worry. That’s especially true if you travel outside the big cities.

I’m not trying to be P.C. I’m just trying to accurately describe our experience. We’ve traveled every corner of Rio de Janeiro state over the last four months (including stays in Rio de Janeiro, Teresópolis, Paraty, and Nova Friburgo), and nearly every day has been a delight.

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Getting our tourist stay extended was anything but delightful. In a recent newsletter, I titled a synopsis of this experience “In the Bowels of Brazilian Bureaucracy,” which tidily summed up our contemptuous attitude toward Brazilian functionaries.

A friend of mine who grew up in Ecuador validated my experience as typical for South American bureaucracy. Mild, even. (It was accomplished in a single day at a single service window.) On the other hand, he noted, you could easily hitch a ride to the next town in someone’s pickup. I agreed with that distinction between government workers and people on the street.

So that begs the question, how does a culture that produces such helpful and neighborly people also produce bureaucratic systems that are so infuriating? The friendly strangers who approach you with helpful tips when you’re standing around looking lost are some of the same folks staffing the dingy police station who seem to make a sport of wasting people’s time.

Whenever I bump up against cultural gripes, I try to think about the flip side of the same coin. As Mark Manson says in his 5 Life Lessons From 5 Years of Traveling the World, the worst thing about a country, culture, or anything really, is also its best. (Coincidently, he uses Brazil as one of his main object lessons in much the same way I’m about to here.)

American Convenience vs. Brazilian Chill

To gain a little perspective, I’m going to compare America’s drive for efficiency with Brazil’s apparent ambivalence for the same.

As Americans, we always expect better. If there is any hint of friction, waste, or disappointment, we assume something is broken. For the sake of future consumers, we leave negative feedback and an honest review.

I felt this firsthand in my previous job as a software developer. In the beginning, I thought I was going to usher in an office worker’s Nirvana of ease and efficiency. Though the software far exceeded early expectations, people were more than capable of revising their standards. New expectations always seemed to outpace progress. In other words, improvement is like money, you never reach a point where you have enough.

That cultural drive to reach for perfection has done marvels to make us the masters of convenience, save lives, reduce wait times, and mint more billionaires than any other country on Earth.

But we who benefit from all that efficiency must also make it happen. That’s why many working professionals (not to mention Amazon warehouse workers, restaurant staff, and just about everyone holding down a job) feel they are running on an ever-accelerating treadmill.

One of the things I appreciate about Brazil is that nothing is perfect. Nobody expects it to be. The sidewalks aren’t maintained. Actually, the pedestrian is thrilled to encounter any sidewalk. Motorcycles follow no traffic laws. Nobody will yell at you if you do something wrong. Everyone’s winging it.

If this sounds a bit chaotic, it can be. But there is a bright side. Nobody expects you to be perfect either. It gives a person like me permission to relax. Work hard, yes. But don’t stress out about all that should have gotten done but didn’t. Lower the expectations. Learn some patience and enjoy life.

It’s a privileged soul that gets to hop off the treadmill at some point in their life. And there’s a reason I chose to spend my time in South America. I needed to chillax! With that in mind, having subtracted myself from the improvement squad, I can’t get too uppity when someone isn’t killing themselves for my convenience.

And with that, our story begins.

Are You Open?

Speaking of convenience, there is nothing less convenient than driving three hours only to find the office closed because of some obscure saint’s day. We decided to call.

In the progression of language skills, calling an official on the phone is the final test of fluency.

Language learning goes like this: first there’s “hello” and “thank you.” Then you can walk up to a store attendant and ask simple questions. Then you can tell a friend what you did last weekend, only slightly botching up the tenses (Liuan and I are more or less at that level of Portuguese). Further along, you can hold your own in a disagreement. Finally, at full mastery, you can call an official and get a yes or no answer to a simple question over the phone.

The call to the police station went like this (translated):

Liuan: Hi. Good afternoon. We need to extend our stay in Brazil. Will you be open tomorrow?

Official: Good afternoon. Where are you from?

L: The United States.

O: Where are you staying?

L: Nova Friburgo.

O: Did you fill out the form and pay the fee?

L: Yes.

O: [Some question we couldn’t understand].

L: Sorry. I didn’t understand. Could you talk slower?

B: [Same question. Same delivery speed].

L: Uhhh… We just want to verify that you’re open tomorrow.

B: … Can I talk to a Brazilian? This is too hard to communicate.

[Flustered, Liuan carries the cell phone out the front door where Jorge is constructing the front deck. By the look on Jorge’s face, he’s thinking this isn’t in the job description. But once Liuan explains the situation he takes the phone.]

Jorge: Hello. This is Jorge, a friend. They are tourists and want to come tomorrow to extend their stay. They want to know if the office will be open.

B: [More indecipherable talking.]

J: They just want to know if you’re going to be open tomorrow!

B: Yes. We’re open from 9 to 4.

J: Thanks. Bye.

Communication will be easier in person, we told each other, trying to comfort ourselves.

The Plan

The biggest puzzle was how to get to the police station in Macaé.

“Private transport will be very pricey,” Bart let us know.

We already knew this. The private transport we took to get to the farm from Rio de Janeiro, also a three hour drive, cost $250. So imagine what it would cost to drive us there three hours, wait for an undetermined amount of time outside the police station (possibly overnight) and then drive back. We didn’t bother to find out.

“So I guess we’re taking the bus?” I ventured. That would entail connecting from the local to the inter-city bus systems. The fact that they operate on sparse schedules and from different bus stations on separate ends of town meant that there was no way to make the round trip in a single day.

“Why don’t we just rent a car?” Liuan suggested. We checked prices online for the basic manual transmission economy car. It was going to be a steal. That would allow us to leave early in the morning, be one of the first in line, and give us flexibility for whatever surprises we would surely encounter.

“Of course! That’s a great idea!” I enthusiastically replied.

It was a terrible idea.

Part I: The Rental

It All Hung on a Signature

Dutra, the farm director’s right hand man, dropped us off at the small car rental shop after a morning hike with the other farm volunteers.

I could tell my Portuguese had improved. It was easy to order up my ride with the customer service rep — nearly three months in — compared with how difficult it was in our first week in Brazil.

Then she gave us the price: $180 for three days. Liuan and I looked at each other shocked. Online, it said $30 (we mistook the daily price for the total, but that still didn’t account for the difference).

It was not the manual transmission economy car we had hoped to borrow. It was their luxury model. But without a reservation, we had to accept what they gave us. Renting a car still beat the alternatives.

The agent printed the contract and instructed me to sign it identical to the signature in my passport. I barely registered the odd instruction. I just signed it.

Wrong! She pointed out all the discrepancies between my passport signature from five years ago, and the one I had just scrawled on the contract. The wide loop back to cross my t’s was tighter. There was a different number if indistinct bumps in my last name. (Flipping seriously?)

“It needs to be exactly the same. They are picky about that.” She printed out another invoice.

This time I slowly etched my signature while my eyes followed every hump and curve of the passport specimen.

It was atrocious. It was like the time I tried to forge my mom’s signature on a second grade homework assignment.

“You can’t sign it while looking at the other one, you have to do it naturally,” she said, stating the obvious. She had me practice on the back of the sheet. Nope. Nope. Nope. Ok, that one’s not bad.

I remembered Bart’s advice about not getting enraged. But the agent and I were both flustered.

She printed a third invoice. I signed. She printed a fourth. I signed.

My tank of optimism was running on fumes. It was conceivable that our modest plan to transport ourselves by rented car could be smoked by my inability to forge my own signature.

“Try again.” She printed another. I signed. It was my best work yet, but it still looked fake.

Mercifully for both of us, she accepted it.

The episode left me feeling unsettled. Was this a bad sign?

The Fear of Dirt

The car was way fancier than the stick shift, compact Fiat we drove around for pennies during our first two months in Brazil.

It had a keyless ignition, a camera for backing up, faux leather seats, and was flawlessly clean. It was a total catastrophe.

I flashed back to the day we turned in our old Fiat compact.

In our last weeks renting that car, we had to park our car on a dark side street. The road construction crew had built a tall concrete curb in front of our driveway. They didn’t fill the gaps in front or back with gravel. The little tires couldn’t get over it.

Coming back from a grocery run, we did not notice that an item had fallen out of the bag into a corner of the trunk. That was understandable since the side street had no lighting.

Several days later we opened the car door and a plume of stench bowled us over. We searched in vain for the animal that had gotten trapped and died inside the car. Then we found the source of the stink: a melted, leaky bag of festering shrimp.

I dumped baking soda all over the trunk and left it for days. Then there was the problem of removing the mounds of saturated baking soda without a vacuum. We solved this by buying a little orange scrub brush to sweep the powder into a pile. Then we used a spatula from the kitchen to shovel it out.

This worked so well we went over the entire interior of the car, that had a layers of dust and sand from the nearby construction and numerous beach excursions with three grubby boys. By the end it looked pretty good. Not perfect. But respectable in comparison to what it was.

When we finally returned our Fiat friend, the agent looked inside with a combination of disbelief and disgust. The only word I understood of her disgruntled rant was sujo — dirty. We had to pay an extra $60 to have it deep cleaned. Embarrassing.

I resolved to return our car as clean as we got it this time. “No shoes in the car!” I barked.

Marooned

We drove the car home on Wednesday. We originally planned to make the trek on Friday to work around some programmed events at Eco Caminhos.

But considering the daily rental cost and the uncertainty we faced, we decided to head out the next day. The first round of presidential elections was on Sunday. Who knew how that would affect things. Plus, we were quickly approaching our first 90 day limit.

That evening, Dutra sent us a very unwelcome text. “Attention, Huska family. It rained a lot today and now it’s raining again. So I don’t think it’s safe for you to drive down tomorrow.”

His warning had the opposite of its intended effect. We checked the weather forecast. It was 100% chance of rain for the foreseeable future.

“So it’s only going to get worse! We need to get it out now or we’ll never get out!” I concluded.

Stuck in the Middle

Before driving down I decided to walk it. The rain pelted my face as I trudged the quarter mile down to the farm’s front gate. Better to be safe and find out where the tricky spots were.

The steep driveway to our lodge was paved in granite, so traction would not be an issue there. But the main road running through the 720 acre farm was compacted earth.

Heading toward the front gate, the road made two switchbacks before nosediving into a straightway that flattened out near the gate. I could just open the gate and let it rip. As long as I don’t brake it won’t slide. I suggesting it to Liuan, only half joking. But the risk of rolling that fast and accidently spinning like a Frisbee into the valley was just too much.

Most of the way, I felt my boots grip the wet, but gritty road. But once I reached the final straightaway, I started to skid. That’s where I was going to have problems.

OK, I’ll try it, I said to myself, but I won’t attempt the last stretch unless I’m perfectly comfortable up to that point.

Liuan joined me for moral support. I inched my way down while riding the brakes. As I suspected, I was able to maintain control past the second turn. But as mud collected on the tires, I started to loose control. I softly skidded to a stop at the last curve before the treacherous straightaway.

A younger version of me would have pressed on. But my almost forty-year-old self knew that it wouldn’t end well.

My shiny, state of the art rental car had mud caked in the wheel wells and sprayed up the sides. But I had bigger problems. Now I was parked in cow pasture. I imagined a curious bull creasing the side door with its horns and shearing off the rearview mirrors with its hulking flank.

With that in mind, I turned the car around and tried skidding my way back up hill, but it was no use. I had to abandon my efforts.

There was no way we were leaving early the next morning.

A Parting of Clouds

We told Dutra we had completely ignored his advice and that he was totally right about the conditions. I was embarrassed to tell him what we had done, but the evidence was parked midway down the side of the mountain.

We wondered aloud how Hilaine, Bart’s wife, drove the kids to school on days when it rained. Did they not go? It seemed they would miss a lot of school if that were the case.

Later the next day, the rain stopped for a couple hours. It still wasn’t perfectly safe, but it was the best window of opportunity we were going to get. We made the controlled skid all the way down to the base of the mountain, about a half mile walk from our rented lodge.

Liuan and I made an valiant effort to clean the tires, wheel wells, and sides with our scrub brush. I really wanted to return the car clean.

The Drive to Macaé

Friday morning we were up at 5:45, ready to hit the road.

Liuan ran up the hill to Bart’s house to get a few last printouts. I had to book plane tickets to prove we were leaving within the extended time period. I would have to cancel them within 24 hours to get the full refund.

We collected everyone’s shoes in a large plastic bag before climbing into the car’s pristine interior.

The drive was uneventful. The countryside was stunningly beautiful, but induced nausea for the backseat passengers. We slowly wound for hours through the mountains of the Atlantic forest before reaching a stretch of flatland as we approached Macaé.

Part II: The Police Station

We rolled into Macaé at 9:30 in the morning. It was dreary, overcast and misting.

The police station was depressing sight. All right angles, drab concrete covered with decades of grime, and an iron fence that made it look like a prison.

A man at the door directed us to a hall labeled “Passaporte.”

We made our way around a small waiting room and headed straight for the service counter.

Sem Sistema

Liuan plopped a worn green folder with a mountain of documents that Bart had printed for us: five perfunctory forms, five receipts proving we paid the $20 fee for each person, five passports, a sham rental contract, plane tickets we planned to cancel as soon as we got home, copies of the relevant pages of our passports, and a recent bank statement proving we had the funds to support ourselves. Those were all the items they might ask for and it was good to come prepared.

While we waited several minutes for someone to check us in, Liuan sorted the mess of documents. Perhaps she thought the all-powerful official who would decide our fate might look favorably on this.

Finally, a man in his thirties came over to ask why we had come. “Did you pay the fee? Do you have the form?” Yes and yes. He flipped through a few documents and then walked off. “The system’s down,” he mentioned over his shoulder.

We stood for an uncomfortably long time at the counter wondering what was next. At first we thought he was going to come back. Then it became clear he wasn’t when we saw him strolling around with no apparent purpose.

Behind the plexiglass, we saw people sitting at their desks and walking around, taking the barest measures to look busy. But nobody else came up to talk to us or to any of the other people already seated in the rows of chairs.

After fifteen minutes or so, a gray-haired man with a friendly face scotch-taped a sheet of paper with big letters on the plexiglass. Sem Sistema — System Down.

The Calculation

We were told to take a seat and wait. Nobody took down our names or gave us a number. So we led our three boys — three, five and eight years old — to a row of seats. Well, this is how it is, we tried to explain. Sucks, but sometimes you have to live with it.

The waiting room was drab and dirty where shoes had scuffed all the walls that nobody bothered to wipe down. We contributed our own filth to the mix. Our shoes and rubber boots sloughed off red dirt clods wherever we went.

Luckily, we had some time since we weren’t tied to the bus schedule. But not really. It would be best if we could tie this up by noon. We didn’t want to have to keep the rental car over the weekend. The small town car rental office only took returns during business hours. Not only that, but the last bus we would need to take after dropping off the car left at 5:20 pm. That added another level of complexity.

A woman stepped up to the counter and let everyone know they could either wait for the system to be back up (and nobody knew when that was going to be), or come back Monday.

Couldn’t they at least take down people’s information? Couldn’t they make copies? Get people queued up so we’d be ready to go when the “system” was back up? Can’t they just stamp our passport and let us go? The people behind plexiglass seemed unconcerned with how long we’d be stuck in this bureaucratic netherworld.

The minutes and hours ticked by as we considered all our possible moves.

What if the system didn’t come back soon? Would we try to do this again next week? Go through the hassle and expense of renting another car? Wake up at 5 am and drive three more hours for another roll of the dice!?! Ugh!!! It almost seemed better just to overstay and face the consequences.

Liuan decided to act.

Checkmate

“I’m going to stand at that counter. If the system comes back I’m going to be the first one there,” Liuan said. She left me with the kids and camped at the service desk.

Liuan is no stranger to callous bureaucracy having traveled to China, so I trusted her intuition.

Soon, a short woman with curly hair came over and said something like, “hey, the seats over there are pretty comfy, why don’t you go take one?”

“No thanks. I prefer to stand here,” Liuan replied. Being belligerent was risky, but what was the downside at that point?

Soon, the older man with the kind face came over and asked how he could help. Liuan gave an ace performance of a desperate mother of three little boys that moved heaven and earth to get here. Would it be too much to ask just to get a little stamp in our passports, even with the system down?

The man rifled through our stack of papers, signaling that maybe he would take our case. He pointed out where we needed to sign. Then he walked off down the hall.

Again, we waited for a painfully long time. Maybe he’s taking a coffee break to gear up for some real work, we speculated.

Twenty minutes later, we wondered if this was yet another false start. But then he emerged from whatever lounge he had hidden in.

“Are you ready?” he asked, in English. HA!!! Are we ready? ARE WE READY!?! Surely, he was toying with us.

This time he scooped up the documents, walked to his office and closed the door. What a relief. It was happening. An entire morning and one of the six officials behind the plexiglass was going to process one family’s papers.

Every five minutes or so, we heard the glorious crunch of a passport stamp.

A half hour later, he returned our passports. We thanked him as fawningly as a war prisoner thanks his captor for sparing his life.

We were good to go.

Carwash

It was 12:30 pm. We had just enough time. It seemed too good to be true.

We got lunch, and drove through all the quaint mountain villages in reverse order. As we entered Nova Friburgo, we started looking for a gas station and a lavo jato — a car wash. After a day of off and on rain and typical Brazilian roads, the car was a dust streaked mess.

At the gas station, the attendant told us to drive around back for a car wash. When shimmied our car through the back alley a man at an adjacent shop told us the car washing guy took the day off.

Sem sistema, we joked.

As we kept driving through town, Liuan spotted another car wash. This one was somewhat automated. It had the spinning spaghetti noodle things. I drove around to the entrance and waited. The operator fidgeted with the buttons. The spaghetti noodle spinners elevated and lowered a few times, but apparently the water wasn’t running. The man looked flustered and apologetic.

We were quickly approaching our return deadline so we bade the hapless operator farewell.

Sem sistema. Again.

We returned the car with few minutes to spare. They charged us for a car wash.

Enlightenment

The ground was soaked. The roads were still slick from days of heavy rainfall. We descended the steep cobblestone driveway from Bart’s house with our wad of documents.

It was Thursday afternoon, the day after our fateful slide down the mountainside and the day before our trip to Macaé.

We arrived at the gate, where their driveway meets the main farm road, just as Hilaine was coming home with the kids in their SUV.

So she did drive the kids to school on rainy days! But how?

“I went out the back gate. The road is good that way,” she responded.

Aha! So the kids don’t miss school. They leave the farm through the back entrance and drive into town using the back mountain roads. That makes sense.

We trudged back toward our lodge on the muddy road.

Several minutes later, Liuan stopped cold. “Wait! Why didn’t we just drive out the back gate?!?” I checked later on GoogleMaps and it was actually ten minutes faster to go that way.

We had risked destroying the rental car and barely sleeping an entire night wondering how many days before we could get it out. But it had never occurred to us (or our hosts to suggest it) to just drive out the back way.

The cows scattered throughout the valley all raised their heads at the loud crack echoing off surrounding hills. That was the sound of our palms simultaneously smacking our foreheads.