So Long, Uyuni Salt Flats. Hello, Moldy Hotel Room.

A three-day detour at the Argentina-Bolivia border showed our family all that money and U.S. privilege can’t buy.

On exactly this day last year, our year-long gap year through South America hit a snag that proved to be indelible in our family’s collective memory. So much so that those of us who can write have each taken a turn writing about it (see Matt’s story and Oliver’s story). Now it’s my turn to try to adequately capture the frustration, fear, bureaucratic dread, resourcefulness, disappointment, and ultimately, resilience and determination that this story includes. It’s a long read, so get your cup of tea ready and come along for the journey!

Triumphant Ascencion

“Llegando al Altiplano. 3,507 feet (11,505 meters) and climbing,” I announce on Instagram, the day I thought our final destination would be the Uyuni Salt Flats.

My family and I are on month eight of a yearlong family gap year in South America. At 4 a.m. that morning, in Salta, Argentina, my husband Matt and I shuffled our three boys out the hotel door to catch a seven-hour bus to La Quiaca. We knew nothing about the town, except that it lay on the border and we would have to walk across a bridge from there into Villazón, Bolivia.

From Salta, the landscape started out lush with humidity from the Amazon that gets caught against the eastern arm of La Cordillera, aka the Andes mountains. As our bus lumbered higher, sleeping dragons of mountains abruptly shed their green foliage skins to reveal striped layers of sediment underneath: burgundy, rust, and light turquoise. The 7,500 foot climb to La Quiaca spread out over such a long distance that it seemed unthreatening. I saw llamas grazing in the flat scrub brush before I realized we’d made it to the Altiplano – the high plain heart of the Andes.

Along with the Instagram elevation announcement, I posted a picture. It shows the back of my middle son Finley’s head as he looks out the bus window at the flat-as-a-bedsheet landscape that meets higher hills in the distance. The color of the sky matches the bus’s window curtains.

I should have learned from another supposedly triumphant social media posting. Years ago, I bragged about my homegrown corn on Facebook, sharing a picture of their tall stalks and fat ears. Tomorrow, I will pick them, I thought. The next morning, I looked out the kitchen window aghast. The stalks were broken at odd angles, with a mess of torn husk and corn silk all around. The squirrels had beat me. Of the ten or so ears I was drooling to eat, I ended up with half of one.

But that memory is far from my mind when I announce our ascent into the Altiplano. When I put down my phone, my oldest son, Oliver, squeaks from across the aisle, “Mama, I feel sick.”

“Maybe you’re carsick,” I suggest. It’s been a common ailment for our nine-year-old on our many winding mountain drives in South America. As an afterthought, I add, “Or maybe it’s the elevation.”

La Puna Strikes

At the beginning of our journey a few months ago, in Brazil, we watched the documentary “Long Way Up.” The actor Ewan McGregor and his friend Charlie Boorman take electric motorcycles from Ushuaia, Argentina to Los Angeles. In La Paz, Bolivia, McGregor gets hit hard by the altitude. One scene ends with a hotel door closing on McGregor, head in hands, about to retch. Even as we traced parts of the friends’ path, the altitude never struck me as something to worry about.

We get to La Quiaca at noon. Oliver can barely walk down the bus aisle and all the color has left his face. “There’s black spots in my eyes,” he croaks. I steady him by the elbows as we step off the bus. Three kids? Check. Five backpacks? Check. One duffel bag? Check. Reusable plastic bag with a cat in pilot gear printed on the front, filled with snacks and random dry good leftovers? Check.

The Altiplano sun, unfiltered by thick layers of atmosphere, scorches our faces. We scurry over to a covered sidewalk past the parking lot. Local women wearing wide brimmed straw hats hawk everything from ice cream cones to dried beans to prickly pear. We set our bags down along a wall and Oliver crumples on top of them.

Matt and I look around, trying to get our bearings. Our task is to get from here to the border crossing at the far end of town, through both countries’ immigration checkpoints, across the bridge, and to the Villazón bus station by 4 p.m., when our next bus for Uyuni leaves. It feels doable, still. Maybe.

An older lady wearing pants—not the skirts and aprons most women around here are wearing— approaches me. “Do you need help getting across the border? I can help you.” I dismiss her offer but point to Oliver, listlessly sprawled on the sidewalk. “Ah,” she nods knowingly. “Go down the street to the pharmacist and ask him for pills for la puna.” La puna, we learn, is another name for the Altiplano. It’s also what the locals call altitude sickness. I leave Matt with the boys, telling him to make Oliver drink some water. Then I bound off down the street.

The pharmacist, when I finally find him, shakes his head. The pills are not for children. “You’ll have to take him to the hospital for oxygen,” he says. Okay, I think to myself. Some oxygen and we’ll be back on track. Back at the bus station, we hail a taxi and pile in with our kids and stuff.

The tiny hospital has seen its share of travelers with la puna, it seems. Staff members quickly usher us to a back room and strap a mask to Oliver’s face. A tube connects the mask to a bubbling bag of water nearby. After a couple minutes, his color comes back. They keep the oxygen flowing for ten minutes. Surprisingly, we don’t owe the hospital anything. They send us on our way as we back out the door stammering gratitude.

The Checkpoint

Another taxi takes us the border bridge. We pay the driver our remaining Argentine pesos—figuring it’s the last time we’ll see this country for a while. Then we lug all our stuff to the back of the line.

Oliver fades quickly. The oxygen only seems to help while the mask is on. Now he’s back to the same state he was in when we left the bus. I get him to the shade beside one of the three portable buildings that serve as immigration offices, lined up in a row along one side of the bridge.

After 20 minutes or so, we get to the first window. “Your visas?” the officer asks as we hand him our passports. Since we left our home in the Chicago suburbs, we have crossed international borders six times, breezing through each one with our United States passports. Being an American citizen has afforded us a level of carelessness when entering new countries. This episode would cure us of that.

Bolivia, it turns out, is one of the few South American countries that require U.S. citizens to apply for a visa. Unlike many of its neighbors, the country is less-than-eager for Americans to sashay in, holding out their wads of cash on the one hand while playing big brother on the other.

I look at the time. Two hours until our bus leaves for Uyuni. To get visas, the officer says, we have to go online to fill out forms and provide supporting documentation for each of our five family members. And pay $160 USD. Per person. In cash. My Claro SIM card that I bought back when we entered Argentina doesn’t work here in La Quiaca, even though it’s technically still within the country. I can’t get an internet connection, no matter how many times I restart the phone.

Futility

Plan B. Matt will go back into town and find a shop where he can get some internet and print out the documents. I will stay with the kids at the bridge. Oliver is still slumped over by the side of the building, just a few steps away from the checkpoint window where I am standing helplessly. I join him, crouching. Our two younger boys have resorted to making a fort with our backpacks. I try to keep their play from spilling out into the line of travelers’ legs. Everyone else, it seems, hands over their documents and gets waved to the next window. How could we be so careless and forget to check if Bolivia required visas?! If my head wasn’t already resting in my hands with a growing headache, I would facepalm myself.

It takes Matt forever, and I’m tired of getting stares from the people in line. I round up the kids and somehow get them and our stuff closer to the road we came in on. We settle on an empty concrete slab with some posts jutting up, perhaps the beginnings of more permanent offices. It must be at least 40 minutes later when I see Matt huffing back. He’s also feeling the elevation.

“I walked all across town,” he reports, between big gulps of air. “The shops are all closed. I asked around at a couple hotels, but they’re all booked.”

It is the Sunday before Carnaval, what we in North America call Fat Tuesday or Shrove Tuesday. It’s a big deal in these parts. When we told an acquaintance our plans to be here during this time, she had warned, “You’ll want to book ahead.”

Now I give up any hope of making our bus to Uyuni. But I’m not ready to give up on a hotel room. What other option do we have? We heave all our stuff and the kids up the hill from the border bridge to the main road. Matt carries Oliver on his back. Oliver’s face is scrunched up—from the blazing sun, from nausea, from the bad news, or maybe from all of the above. Tears roll down. “I can’t walk. I can’t go anywhere,” he pants.

“We’ll get a taxi, sweetie,” I reassure him. But the road is deserted. After a few long minutes, a car passes, but it doesn’t stop for our flailing. Another. And another. Finally, a driver stops. I freeze. We don’t have any more Argentine pesos. The driver surely won’t take a credit card.

I decide it’s better to cross the payment bridge when we get there. We hop in the taxi. When we arrive back at the bus station, I pull out a US five-dollar bill. Our last ride cost the equivalent of about two US dollars. “Will you take this?” I ask. “We have nothing else.”

“Well, I don’t know the exchange rate,” the driver says. “But okay.” As we unload our stuff, Matt gripes about how I always try to spend down our currency when we leave a country and how it has now backfired.

“We’re always going to keep some for emergencies like this from now on,” he says. I don’t disagree.

The Hotel

Around the time our scheduled bus rolls out of the Villazón station on the other side of the border, we find ourselves back where we started, at the La Quiaca bus station. Just like the first time, our backpacks line up in a pile against the wall and Oliver is still slumped over them. I look around for the lady with the pants. That’s why she asked us if we needed help crossing the border, I realize. We must have looked as clueless and unprepared as we were. She is nowhere to be found. If I had found her, I would have contracted her services in an instant.

Now it’s my turn to run around town while Matt stays back with the kids. Mission: keep my family off the streets tonight. I retrace my path toward the pharmacy, remembering a gaudy orange building with a hotel sign somewhere around there. There it is. The lobby is empty. A folk music video blares from the TV. I beeline for the woman behind the desk. Yes, they have a room. Thank God.

I walk back victorious to the bus station, stopping along the way for a couple sandwiches. We’ve only eaten snacks from our cat bag since we left Salta this morning. Then we lug the kids and our stuff the block down to the orange hotel. We wait in the lobby while two women prepare our room. Meanwhile, Oliver’s body has had enough. “I have to throw up!” he screeches. I look around.

“There, throw up in that planter!” I hurry him over to a poor unsuspecting houseplant and he heaves violently and repeatedly into its soil. I apologize to the plant. Matt apologies to the hotel attendant.

Our room is up two flights of stairs and down the hall. My chest heaves from the exertion. Four single beds line up in a row going to the window, which faces another building across the street. At the window, I look up. Black mold blooms from the corner of the ceiling. It doesn’t matter. Having somewhere to rest our heads tonight is enough.

The Plan

We put the kids down for naps and then set to work on our laptops. Thankfully the hotel has Wi-Fi. The first piece of bad news we discover: there are no more buses to Uyuni until the day after Carnaval. That’s still three days away. By then, we are supposed to be headed to our next destination, Sucre, where we have already reserved and paid for an AirBnb. We could just cross the border—whenever we manage to do that—and try to find five seats on the next bus to Uyuni or hope there is some kind of private van transport available. But if there are no options, we’ll be in the same situation as we were in an hour ago—looking for a hotel room during Carnaval. But that’s not our biggest problem.

Our biggest problem is that we’re low on cash. We started our yearlong journey with a couple debit cards and about $1000 US dollars. When my mom visited us from Texas, she brought us a few thousand more US dollars because we were about to enter Argentina, where skyrocketing inflation has created a two-tier exchange rate. On the black market, you can exchange 1 USD for about 300 Argentine pesos. But if you go through official means, like credit cards or bank ATMs, you get about half as much—1 USD for about 170 pesos. Since we first entered Argentina three months ago, we have been exchanging away all our US dollars on the black market. Now we are out of pesos. We have about 400 US dollars left.

At the border bridge, the officer was clear: they only accept US dollars or Bolivianos to pay for visas. No credit cards, either. If we went to an ATM in La Quiaca and ate the crappy official exchange rate, we would still only be able to take out Argentine pesos. So, we are left with the option of using our remaining US dollars. This will only cover two family members.

Oliver awakens to a litany of curse words from me and Matt as we run through our dead-end options. Though we have tens of thousands of dollars sitting in bank accounts back home, that doesn’t help us now. We are stuck in a situation that neither wads of cash nor U.S. passports can buy us out of.

Finally, we decide. We will skip the Uyuni Salt Flats, even though that’s arguably the number one sight to see in Bolivia. We’ll go ahead and book new bus tickets in three days going to Sucre, our next stop, to put us back on our original schedule. And, for the days that we were supposed to be taking eye-popping perspective photos on brilliant white salt expanses, we will stay here, in a no-name town at the border, figuring out how to get visas for our family of five.

For the currency situation, our plan is this: I will get my visa first—tomorrow, hopefully—with our remaining US dollars. Then I will walk across the bridge into Bolivia with the debit card, find an ATM, and take out the necessary amount of Bolivianos to get the remaining visas.

And for the rest of the time, I guess we’ll be watching La Quiaca’s Carnaval celebration from our hotel window.

PSA: Don’t Google Medical Concerns at Midnight

As the sun sets, I walk back across town to the border bridge to make sure the immigration checkpoint will be open tomorrow and ask a few more questions. I want to be sure I get the paperwork right this time, and I don’t trust that I’ll find the right intel online. My lungs hurt just from walking.

Groups of dancers mill around at street intersections, already beginning the festivities. A gaggle of squat older women in black bowler hats swish their brown shawls and dark blue skirts. A younger woman adjusts her white and gold hat, which matches her mini-dress and thigh-high boots. Young people in white shirts and red ponchos are paired off boy and girl. They run around a traffic circle to the sound of trumpets and drums, waving flags. We’ve been told that in some Carnaval hot spots, like Oruro, Bolivia, families will save for an entire year to pay for their Carnaval costumes. La Quiaca is no Oruro, to be sure. But they’re putting in a valiant effort.

At dinner, we order from the hotel café downstairs. They have a set menu, which includes tough chicken, a pile of white rice, and soggy fries. The five of us can’t finish even two plates. I put the leftovers in the plastic Tupperware that I’ve brought along from home, in case someone has a case of midnight munchies. Oliver has another episode of projectile vomiting, this time into the bathroom toilet.

At night, I toss around on a mattress on the floor. What a day. As I review all that we’ve been through, it dawns on me that maybe I should be more worried about Oliver’s altitude sickness. He’s been sleeping ever since we got to the hotel, looking like a tenth of his normal self. But with all the fuss about buses and visas, I’ve barely had a chance to think about him. Now, in the dark, moldy hotel room with everyone else asleep, my anxious mom brain turns on. What if he takes a turn for the worse? What signs should I be looking out for?

Unfortunately for me, I have Google at my fingertips. I look up “altitude sickness kids serious symptoms” and turn up this warning: “The symptoms of acute mountain sickness usually appear within the first day or so of reaching a high altitude. More severe forms like HAPE or HACE take longer to appear, usually between two and five days.” HAPE: high altitude pulmonary edema, when your lungs start to fill with fluid. That’s bad. HACE: high altitude cerebral edema, when you brain starts to swell. That’s really bad.

That’s it for me. I can’t sit with these possibilities alone in the dark. I wake up Matt, who has been sleeping soundly. I read him my findings. We creep over to Oliver’s bedside, where he’s snoring open-mouthed. I look for blue color around his mouth, a sign of oxygen deprivation. His color is not rosy, but it’s not blue either.

“He doesn’t look like he’s suffering,” says Matt. “I mean, I think we would know if his lungs were filling up or his brain was swelling.” We consider our options, again.

It’s midnight. Oliver appears to be breathing normally and sleeping soundly. The hospital is closed. Even if we wanted to get down to a lower altitude, which would have to be back the way we came, there are no buses running in the dead of night. The only thing to do is wait it out until morning and hope for the best.

Matt and I both don’t fall asleep for hours. We each lay awake in our single beds, imagining worst-case scenarios and battling our own inner demons.

The Checkpoint Virgin

In the morning, Oliver seems better.

“Why’d you have to wake me up and make me think of all the bad things that could happen?! I was up until, like, 3 a.m.!” Matt says.

“Well, it felt better for me not to bear all that alone!” I shoot back.

It’s Monday, the day before Carnaval. Our goal today is to print all the documentation we need for visas and send me across the border on a cash-securing reconnaissance mission. With the boys in the hotel room watching “Shang Chi: Legend of the Ten Rings” we manage to find an open stationery shop and get our papers printed. Next stop: Bolivia.

Back at the border bridge, I tell the officer my sob story. I just need to get myself across, so I can get cash, then I need to come back into Argentina and get the rest of my family across. He purses his lips and scans my papers. Then he walks out of the portable building and waves for me to come with him. I follow him over the bridge. It’s that easy?!

On the Bolivia side, he leads me into a building that must be their main offices and into a back room, where he hands another man my papers. I’m told to wait in the hall. From my vantage point, I can see the back of an immigration officer at a desk behind plexiglass. People wait in a line that snakes out the door. Some are here to get passports. Some are here for business I don’t understand. One elderly couple who are clearly Indigenous are told they need to get their Carnets (identification cards) updated before they can finish whatever they’re here for. An officer pulls them to the side to explain the step-by-step instructions. Their faces show the same bewilderment and overwhelm that we felt yesterday. Bureaucracy knows no borders.

In the hall, a statue of the Virgin wearing a lacy pink gown and white veil is set back into the plastered wall. Her eyes are downcast and one cupped hand pokes out of the folds of her dress. Is she, also, hastily reviewing her documents and hoping they’re in order? Is she receiving the desperate prayers of the people in this room, right now, all dependent on the whims and digestive states of each individual immigration officer? I add my own prayer to those of so many others.

The officer comes out. Everything is in order. But the payment I included—two hundred-dollar U.S. bills—is not passable. One of the hundred-dollar bills has a slight tear. They won’t take it.

I pull out the two other hundreds that I thankfully also brought along. Take them, any of them, even all of them! I think. The officer inspects each one meticulously, holding them up to the light, fingering the edges.

“These two will do,” he says. Thank the Virgin!

He waves me into the back office, where he affixes a visa sticker to my passport and punches an entry stamp. It’s the most beautiful sound I’ve ever heard. Then I’m let loose into Bolivia.

The street going up into town from the bridge is lined with shops. I stop at store selling SIM cards and get a new one for Bolivia. The first ATM I find is out of order. A few blocks up, a second one has people waiting in line. When it’s my turn, I hold my breath and put in my debit card. It won’t allow the amount I request. It’s too large. I keep trying lower amounts until, finally, the machine spits out a wad of Bolivianos. Success! Then I go through the process three more times to get the necessary amount of cash. When I open the glass doors, I apologize to the line of people waiting. I inhale a lungful of thin mountain air. We just might be able to cross the border as a family after all.

Back at the border, a line of travelers wait to enter Argentina. As I walk across the bridge, I notice people crossing by foot in the muddy brown river below, packs on their backs. The hotel owner had told me about this. Locals often cross this way, without official documentation. We could do it too, he had said. But if we had, we’d be in hot water once we tried to leave Bolivia.

The funny thing is, it’s happening in plain sight in front of all the immigration buildings. All the trouble we have gone through, and we could have just walked across the river.

Carnaval, La Quiaca Style

We find a hole-in-the-wall place to eat a cheap lunch, and then it’s back to the bridge to get visas for everyone else. They get them without a hitch. Now we have two more days of waiting around in La Quiaca before we need to cross over to catch our next bus.

The boys watch more movies. Matt gets some remote work done. Each evening, we look down from our hotel window at the street, where groups of Carnaval revelers in matching outfits toot their horns and march.

On Fat Tuesday afternoon, we take the kids to the plaza down the street, where a concert platform has been set up and loud Andean music blares. Kids are armed with bottles of colored spray foam, which they gleefully deploy on one another. Some moms have dressed their kids in clear plastic rain covers, anticipating the onslaught. Oliver is well enough by now to climb up and down the playground equipment. I shell out some money for an old man to hand-crank a merry-go-round for the kids to ride. He also gives us a few balls to play at the foosball table. We stop at an ice cream shop on the way back to the hotel to celebrate our last night in La Quiaca.

The next morning—Ash Wednesday—we eat our last breakfast at the hotel café. Like always, it’s coffee for the adults, hot chocolate for the kids, and a selection of various breads delivered from a nearby bakery. We have time to kill—our bus doesn’t leave until 8 p.m.—so we wander around town trying to find a barber. Everyone’s hair has gotten unruly.

Wiser

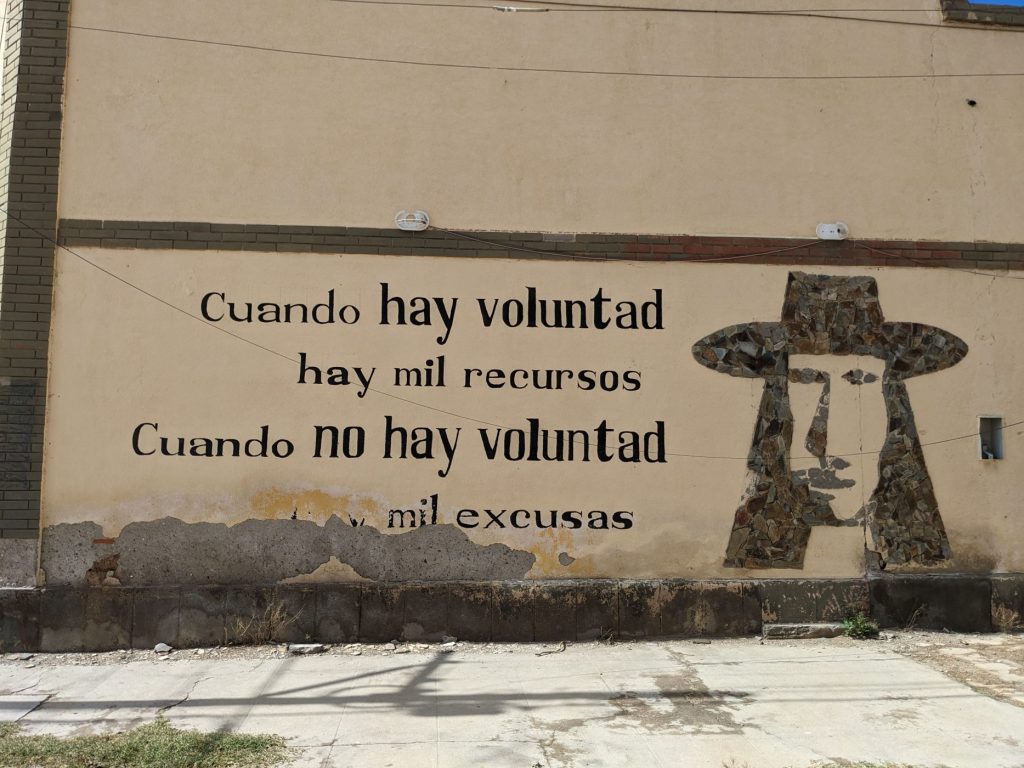

We’re unsuccessful, but we do find a piece of street art that speaks to us. A silhouette of a man with long hair and a top hat is painted across a wall with the words, “Cuando hay voluntad, hay mil recursos. Cuando no hay voluntad hay mil excusas.” Translated, it says, “Where there is a will, there are a thousand resources. Where there is no will, there are a thousand excuses.”

We laugh ruefully, trying to explain its meaning to the kids. We had a will to cross the Argentina-Bolivia border. At one point, on that first afternoon, we had contemplated jettisoning the Bolivia portion of our trip entirely and heading back into Argentina. But I was intrigued by Bolivia—the high plains Indigenous cultures, the stark landscapes, and the altitude itself, which seems to be part of the grit and spirit of the land. We could have taken our roadblocks at the border as an excuse to turn around. But we found resources—internal and external—to persist on our journey.

After lunch, all five of us successfully cross the bridge. “The promised land!” we ooh and aah. We’ve waited three days for this moment.

We spend the afternoon in another hotel room, a newly built building that is half-finished on the outside, across the street from the Villazón bus station. As the sun sets, we gather our five backpacks, one duffel bag, one cat bag, and three kids once again and walk in the dimming light towards the station. The road unfurls before us, daring us to keep going. We accept the challenge.