Sickness and Unpreparedness Upend Plans at Bolivian Border

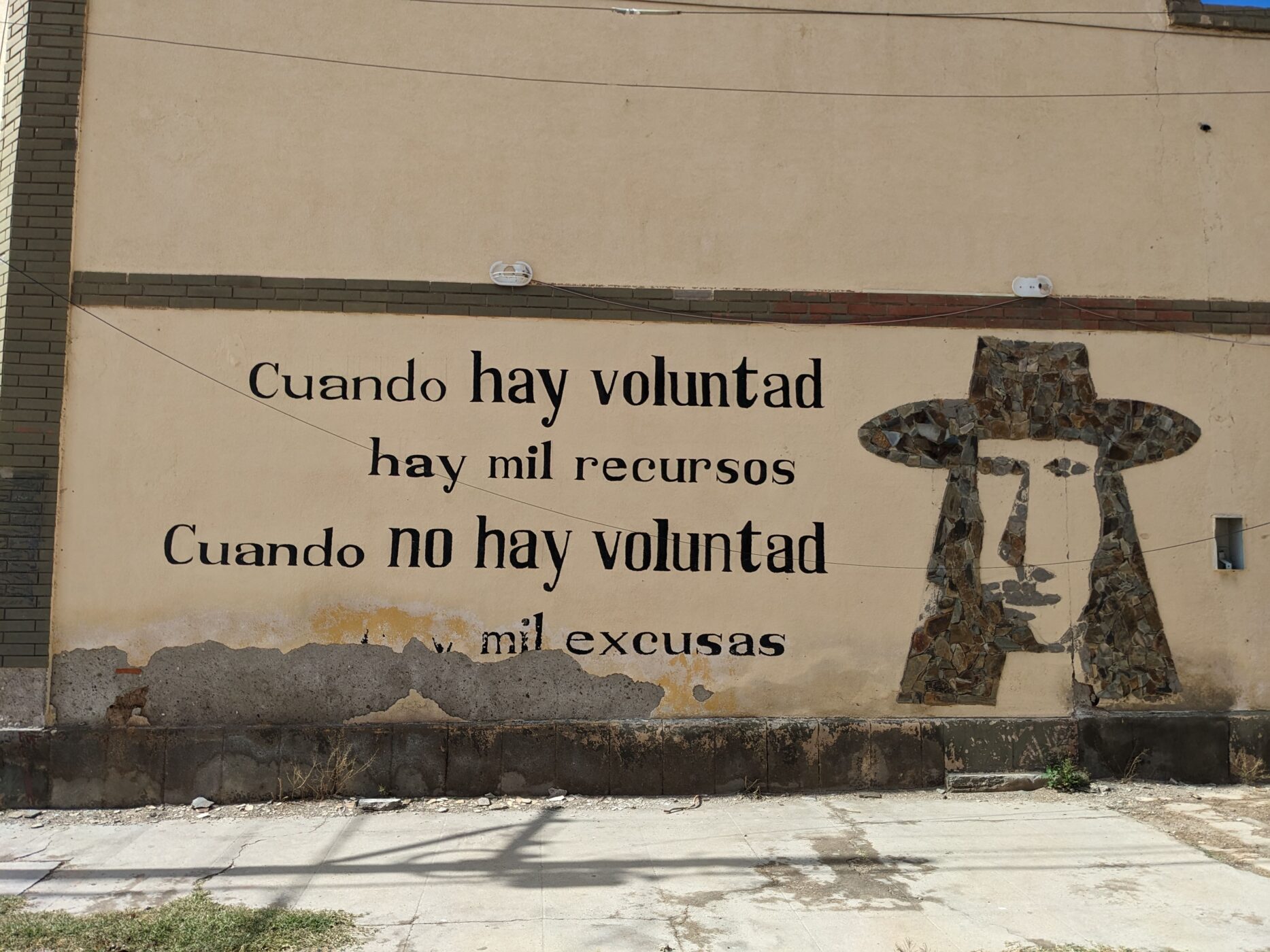

The photo above translates as, “Where there is a will, there are a thousand resources. Where there isn’t a will, a thousand excuses.” We encountered this mural in the morning just before crossing into Bolivia after four days of overcoming a series setbacks. It spoke to us. The following is the story of our adventure at the Argentine-Bolivian border.

Unprepared

It was our turn to present our passports at the pedestrian border crossing to stamp out of Argentina before entering Bolivia. Oliver, our nine-year-old, sat on the curb motionless with his head down, trying not to throw up from altitude sickness. We still had three hours to catch our bus across the border which would take us to the Uyuni Salt Flats.

The Argentine official asked us if we had our Bolivian visas. No, we did not! Were we supposed to? “Well, I can’t stamp you out of Argentina if you aren’t prepared to enter Bolivia.”

Oh crap. I’ve learned that the best thing to do when hitting a bureaucratic roadblock is to lean on the official’s expertise; arguing is useless. “What should we do?” I asked.

“Let me take you to my compañero in Bolivian immigration.” She stepped out of a side door in her grey shipping container office and led us to the first in a series of blue shipping containers — the Bolivian offices. I knew it, I thought, there’s always a way.

But the Bolivian official needed documents: filled-out visa applications, yellow fever vaccine cards; copies of hotel reservations and flight itineraries. “I can’t give you a visa without an application. Go find a kiosk in town that can print your documents.” He came off as sympathetic, albeit without the liberty to let us through just because we came unprepared.

Altitude

Earlier that morning — 3:50am to be precise — I switched on the lights to our apartment in Salta, Argentina. I took sadistic pleasure in the rude awakening I gave my wife and kids.

Our bus to the border town, La Quiaca, left at 4:40am. We would arrive there at noon, cross the border into the Bolivian town of Villazón, and take another bus to Uyuni at 4:00pm. That would give us four hours to figure out the border crossing.

Our three-year-old, Miles, was oddly chipper. He sang “Wake me up before you go, go!” — a song I didn’t even know he knew. The rest of us were barely awake.

We all slept the first half of the bus ride and woke up to the sunrise illuminating the painted mountains. Oliver complained that he was feeling carsick. We told him to stop playing on the iPad and look out the window.

As we got closer to La Quiaca, Oliver felt even worse. I noticed I was feeling short of breath. Liuan confirmed that we were quite high. La Quiaca sat at an elevation of 11,290 feet!

By the time we got off the bus Oliver could barely stand. He claimed he couldn’t see. His lips looked slightly blue.

Oxygen

The sidewalk in front of the bus station was a bubbling stew of tourists hailing taxis, money changers, old ladies with carts selling ice cream and fruit, people with bundles and parcels engaging in cross-border commerce.

We found a spot along the wall to dump our backpacks and let Oliver catch his breath. He slumped over onto the baggage, eyes closed, face ashen.

Moments later an old woman, who had doubtless witnessed this scene countless times before, gave her advice. There’s a pharmacy down the street. Ask for medicine to treat puna. Make sure to let him know it’s for a child. If that doesn’t work, take him to the hospital and they’ll give him oxygen.

Liuan left the scene to look for the medicine. She came back empty-handed. They only had medicine for adults.

We both looked at Oliver, splayed out lifeless over the backpacks. It was clear what we had to do. We hailed a taxi and instructed the driver to take us to the hospital.

The Hunt

The oxygen brought Oliver back to life. At least temporarily. All of us at this point were suffering to some degree. Liuan felt queasy. I had an throbbing headache and felt short of breath. Regardless, I carried Oliver on my back while Liuan shouldered the extra luggage.

We hailed another taxi outside the hospital, this time to the border. We still had three hours. It seemed like more than enough time, though it would soon prove to be too little.

At that point, we thought we had passed through the worst of this adventure. Every other border crossing (Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Chile) had been laughably easy. Just show up, give them our stack of passports. Sometimes they asked for a hotel address and stamped our passports. Other times they just entered some data and waved us through.

What we failed to realize is that Bolivia requires as visa ahead of time. For Americans, that comes with a $160 fee per person. That comes to $800 for a family of five. (Fair enough when you consider what a Bolivian must go through to get into the U.S.)

The way the Bolivian official made it sound, I could just walk back into town and somehow prepare all the documentation and get it done.

I had no choice but to try. Liuan and the kids stayed behind, camping out at the margins of the immigration area.

Typically, Liuan is better at those types of things. She knows the right questions to ask, and has a sixth sense for whom to ask. (An exception being the time she asked the drunk guys in Uruguay for directions, but that’s another story!) My superpower, on the other hand, is speed-walking. I can cover a lot of ground fast.

I hustled back up the hill into town and started asking everyone I could find for a place with internet and printing. I was directed to a libreria. It was closed. Another guy directed me to a document printing service across from the Banco Nacional. Both the bank and the printer were closed.

I decided to try my luck on the other half of town. I raced around, following leads. I stopped a young woman in the middle of a street market. She directed me across the park where I would find a Banco Nacional, and a printer right nearby. It was closed as well. (That “second” Banco Nacional was actually the same one I had visited earlier, but it would be a couple days before I would have that mind-blowing epiphany.)

Undeterred, I crossed the street and approached a woman running her tiny hole-in-the-wall convenience store. She leveled with me. “It’s two o’clock on a Sunday. Plus it’s Carnaval [a multi-day celebration before the start of Lent]. I don’t think you’re going to get much done today.”

No Room

A twinge of panic overtook the hope had animated me up to that point. We weren’t going to cross into Bolivia that day. The bus connection was a lost cause. We wouldn’t be arriving safe and sound to our reserved room in Uyuni.

I backtracked across the park where I had seen a few hostels and inns. I rang the buzzer to one: no rooms. I entered another. An ornery old woman asked if I’d seen the sign on the door that said completo. No I hadn’t, sorry. Four or five such attempts yielded the same result: nothing.

The twinge of panic blossomed into a wave despair. I called off the hunt. I had to let my family know the bad news. I’d failed at getting the papers. We had nowhere to rest our heads. As I walked back, dejected, I imagined us all passing the night huddled behind a bush.

Back to Town

To make things worse, we had no Argentine cash. We intentionally spent it all thinking we no longer needed it.

Liuan took the news calmly. She seemed to have already intuited that our chances of keeping our itinerary were vanishing.

We decided to walk back into town instead of taking a taxi. We couldn’t have paid the driver anyway. Oliver walked up the hill while I carried his backpack. He started whining. “How long do we have to walk?!? I can’t make it!”

“You will make it because you have to!” I said firmly. “Sometimes things don’t go to plan. But you have to carry on and do what’s necessary. Now we have to find a place to stay if we don’t want to sleep in the street! That means we have to walk to town.”

Then I remembered that he just left the hospital an hour ago. I asked him how we was feeling. He said his eyes were filled with black spots and he could barely see when he was standing up. “Oh, never mind then! Sit down,” I backtracked.

He plopped down on the curb of the desolate divided thoroughfare with his head between his knees. “I’m so sorry I’m like this, Baba.” Tears dripped onto the asphalt.

My heart melted. I sat at his side and wrapped my arms around him. “It’s not your fault you feel sick. We’ll make something work.” I was out of ideas.

Dollars

After some brainstorming, Liuan and I settled on hailing a taxi and hoping the driver accepted dollars.

The driver asked where I wanted to go. I didn’t know.

“What are you looking to do?” he helpfully reframed the question. We needed to find a hotel and change money.

He decided we should go to the bus station. There we could change money. Hotels were nearby.

When we pulled up to the bus station, we let the taxi driver know we didn’t have the approximately $1.50 in Argentine pesos, would he take dollars? He said he didn’t know the conversion. Liuan waved a $5 bill and he accepted.

We piled our backpacks against the wall and Oliver slumped over the pile. It was the same spot we had occupied over an hour ago when we first got off the bus.

Liuan changed a couple hundred dollars into pesos and then walked down the block and got a room at the first hotel she tried (of course!). As Liuan checked in at the front desk, Oliver puked in a planter in the hotel restaurant.

Options

We hauled our stuff to the second floor, Oliver on my back, and put the kids to bed.

Liuan wanted us adults to take a nap too. But I informed her we would be back on the street by ten o’clock tomorrow and we should probably make the most of the free Wi-Fi, private space, and daylight hours to decide on a plan. She reluctantly saw my point and joined me at the little table to mull over our options.

I looked up bus tickets for the next day. Nothing came up. I tried the day after (Tuesday). Still nothing.

There were only two buses per day that went to Uyuni and they were booked out. I looked at Wednesday. There were openings. But Wednesday was three days from then and we were supposed to be leaving for Sucre then. We would have to cancel our reserved hotel and the salt flat tour.

I looked for direct buses to Sucre. It was the same. No openings until Wednesday.

Liuan messaged the bus company to see if an agent could pull some strings. “Sorry,” the agent replied, “it’s Carnaval, everything is booked out. No chance.”

Bolivia can be seen in the distance, so tantalizingly close.

A Bigger Obstacle

Maybe there was private transport to Uyuni? I Googled it and nothing came up. (It turns out there was. We saw it once we eventually crossed the border. Google isn’t very useful in this corner of the world.)

We were getting nowhere figuring out how to get to Uyuni. Instead, we turned our attention to the visa. I found the website with the form. It required 3×3 passport photos. Now where on earth was I going to get that??? (I found a helpful website that automatically takes a normal face shot and transforms it to the proper specifications.)

Then there was the $800 visa fee. “I would assume we can pay with credit card?” I said uncertainly. Considering where “assuming” had gotten us, Liuan decided to run down to the border crossing and ask while I worked on the documentation.

She came back twenty minutes later, out of breath. Only cash. American dollars or Bolivianos. We only had $500 USD in cash. Another brick wall.

There was no way to get more USD without someone mailing it to us. There was no way to get Bolivianos without crossing into Bolivia. The only currency we could get with a debit card in Argentina was Argentine pesos! (Oliver recalls waking up from his nap around this time and hearing a string of cuss words — in his words, “I woke up and all I heard was f*ck, sh*t… coming from across the room.”)

Despite having booked over a month’s worth of bus tickets, Airbnb reservations, and a semi-expensive flight from La Paz, Bolivia to Bogotá, Colombia, I seriously considered cutting our losses and abandoning our trip to Bolivia.

The Clouds Part

Most of our bookings in Bolivia were cancellable. Except for the flight from La Paz, which wasn’t a small amount of money. On the other hand, if we bypassed Bolivia, we wouldn’t have to pay the $800 fee for the visa.

I searched Skyscanner for flights from anywhere in Argentina to Anywhere. But we started counting up the cost and hassle of going that route. It would require us, at a minimum, to take the eight-hour bus ride back to Salta. There probably wouldn’t be openings for several days. In the end, skipping Bolivia would be as difficult and more expensive than trying to catch up with our prior itinerary.

After several frustrating hours of disappointments, dead ends, and involuntarily spewing curses, Liuan and I came up with a plan that would allow us to sleep at night.

First, we made the difficult decision to sacrifice the three-day stay in Uyuni. That would be a big bummer, for sure. But clearing that from our itinerary would allow us to stay where we were an additional two nights. It would allow Oliver to recover.

Second, we would snap up those Wednesday bus tickets to Sucre. We would arrive at the same day and hour as we had planned previously.

Now we had three whole days to work through the visa problem. We would out-stay Caranval and take all the steps to prepare our visas with plenty of buffer for setbacks.

We also determined how to get the cash to pay the fee. The next day, one person would get the visa and cross the border and come back with enough Bolivianos to pay for the rest.

We had tamped down sense of urgency. Now we could get some much needed sleep.

We were never happier to be able to check in to a hotel room.

But the crummy Wi-Fi forces me to abandon the effort.

What Kept Me Awake

The room smelled funny. Black mold splattered the ceiling on the far end of the room. Sewer gas wafted from the bathroom. When I finally stretched out on that small bed with the caving mattress, I never felt so thankful in my life for a place to sleep.

I was quickly drifting off when Liuan whispered from her mattress on the floor, “Are you awake?”

She was sitting up, her face was illuminated by the blue glow of her phone. “I’m worried about Oliver.”

I gazed long and hard at him, looking for a sign that he might be suffering. He was out cold but breathing peacefully. “He looks fine. Sleep will do him good,” I tried to reassure her.

She let me know that altitude sickness can be life-threatening. She started reading of frightening and unpronounceable maladies like cerebral edema and pulmonary edema. “I just want to know what signs to look out for in case we need to get him more medical attention,” she responded when I asked why on earth she was Googling this.

I tried to reassure her some more. He didn’t appear to be in distress. Sleep would help and he’d likely wake up feeling better. But in my mind, I knew if he took a turn for the worse, there was nothing we could do.

We would go to the hospital at the first sign of distress, sure. But after seeing that hospital I doubted they had the expertise to keep him alive if fluid was filling his brain or lungs. The next large city was a seven hour drive. Not that there was a way to get there in the next several days.

Liuan, having unburdened herself, promptly fell asleep.

I on the other hand laid wide awake imagining the dark possibility of losing my firstborn son. Oliver, whom I lent my finger to squeeze when he got his first shots just minutes out of the womb. Who “worked” by my side as I fixed up our house through the years. Who spent almost his entire childhood anticipating our “world travels,” as we used to refer to it.

I hated myself for taking this stupid gap year. For deciding to wander off into a place so remote, so out of reach from the developed world. For not simply Googling the requirements for entering Bolivia ahead of time. Idiot! How could I have been so careless?

Now my son might die in his sleep, and we won’t even be able to leave this little dusty border town until the end of Carnaval!

Things Start Working Out

In fact, Oliver woke up the next morning feeling better.

I had gotten about three hours of sleep. But I didn’t feel too shabby.

We ate our simple hotel breakfast — coffee and croissants — then Liuan and I set out armed with a 28-page pdf document to find a printer. It turned out that, despite it being Carnaval, some people opened their shops for a few random hours throughout the day.

We had no trouble finding a printer at a libreria, which, despite translating as “bookstore”, did not sell books. It mostly sold school and office supplies and some other random things (like long garish eyelashes that teenage girls wore for the Carnaval celebrations). Most importantly for us, they did prints and photocopies.

When Liuan booked an additional two nights at our hotel, El Hotel Frontera, she also asked where to get Bolivianos, hoping there might be a place in town. As we suspected, you had to get them in Bolivia. But the hotel manager informed her of an illicit route to bypass the official checkpoint that the locals used all the time.

Tempting as it was to go rogue, we decided Liuan should enter legally as a test case ensuring that we had all our documents in order. It would be better to find out sooner if we were still missing something.

Liuan successfully got her Bolivian visa, crossed the border, and found an ATM to withdraw more than enough Bolivianos to cover the other four visas.

The only minor hiccup was that the official demanded that the dollars she used to pay for her visa be in mint condition. Liuan first handed him two one-hundred dollar bills. He rejected one because it had a small tear. She handed him a fifty and a twenty. He didn’t like the twenty because it was folded. She told him that’s all she had and, after what seemed like an eternity of holding her breath, he accepted it.

The city on the other side of the bridge is Villazón, Bolivia, or as we called it “The Promised Land”.

The divided highway nearby in the photo is where Oliver sat on the curb and couldn’t go on.

The Big One

Before we left for our gap year, I expected we would confront the “big one” — an instance where we screwed up or got screwed over so badly that we would be left with few options, desperate and vulnerable. Given the length of time we were traveling, something was bound to happen.

My all-time worst travel fail was the time I lost my passport in Mexico. It’s the low bar I compare all other travel (and life) fails to. In a way it was more tolerable since I wasn’t going through it alone this time. In another sense, it was harder because of the suffering it inflicted on my child.

I believe with all my heart that this was the “big one” for this year of travel. Some other candidates included losing my wallet in the first week (though it was found the next day) and the Brazil visa extension saga. There was also the time we missed our ferry to Uruguay and had to hustle around Buenos Aires with our luggage to catch a different ferry at another terminal. But after the fact, those other setbacks didn’t seem like the absolute low point. There was always some element of luck that bailed us out from the worse outcome.

This, I believe, was the big one. The low point. The nadir. If there is a worse one to come, God help us.

Unlike the Brazil odyssey, I can’t even get sore about “Latin American bureaucracy.” This was our own fault. We got complacent. The other six borders we had crossed had required no advance planning.

Plus we were traveling fast. We should have been thinking about Bolivia the week before while we were Santiago, Chile. But with a bus-ride crossing the Andean border into Argentina and an early morning flight to Salta ahead of us, our Bolivia plans seemed safely in the future. We would cross that bridge when we got there. Literally.

Lessons Learned

As we crossed the bridge into “the promised land,” as we were calling it, we saw a stream of people fording the shallow puddle of a river in plain view of the border officials. That was the illicit border crossing the hotel man was talking about!

The first takeaway was a practical one: border crossings are important. Research it ahead of time.

Safely back on track in Sucre, Bolivia, we dined at an upscale restaurant and went around the table sharing our takeaways from our difficult experience. Liuan felt that the experienced showed how even the most difficult problems are solvable by working together as a family. The kids talked about how they learned about Carnaval and altitude sickness. I struggled to put my takeaway into words.

Maybe it’s easier to describe what the experience was by what it wasn’t. I had more than enough money to solve the problem, but I couldn’t use it. I couldn’t reroute my way out of the problem by renting a car or paying for a last minute plane ticket. I could afford a nice hotel with good Wi-Fi, but I had to be happy with whatever was available. For a brief and solitary moment in my life, I experienced what was like to have no options.

It was a terrifying feeling, especially when I consider the ways it could have gone worse. But it’s one of those hard lessons that come with the travel package that you nevertheless treasure. It lowers the bar for what inspires feelings of gratitude: a good meal, a hot shower, another day with the people you love.