When You’re the First Tourist in a Remote Chinese Village

An excursion off the beaten path lands us in a village with no tourist services where we find a local family to eat and stay with. How do we reckon with being harbingers of tourism that will undoubtedly change the village?

After a white-knuckle bus ride around precipitous mountain bends, the unreliable machine spit us out, disoriented, in the middle of the gorgeous Long Ji (龙脊) rice terraces of the Guilin province. It was 2009, and Matt and I were here on honeymoon. An overseas plane, cross-province train, overnight bus, and several local bus transfers from our home in Chicagoland, and here we were in a relatively remote part of China, about to enter a Red Yao (one of the non-Han ethnic minorities) village.

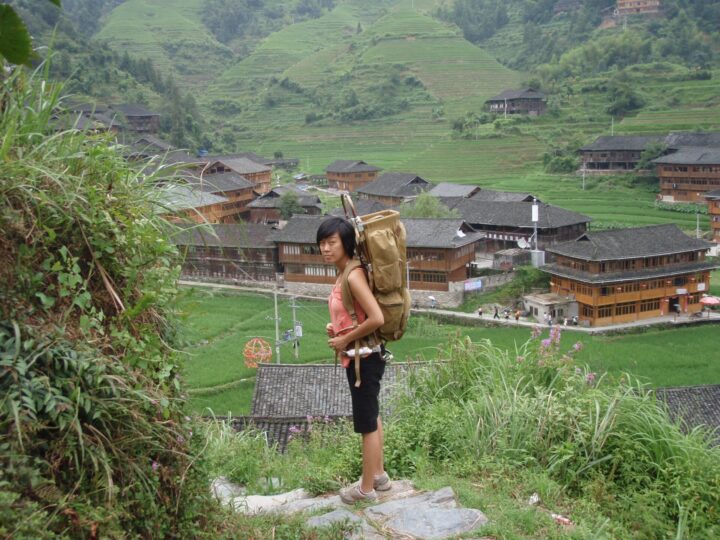

First, we had to lug our backpacks two kilometers up the steep trail from the bus drop-off. Well, I tried to. But an older Yao woman immediately latched onto me and offered to carry my pack. I valiantly refused, and she doggedly followed. “Just 50 kuai! 45! Okay 40!” Her desperate bargaining chipped at my resolution to be independent and cheap. Somewhere about halfway up the trail, at about $5 USD, I gave in.

There was one hotel in Da Zhai (大寨), our destination. It was more like a wooden barn with three floors and rickety wooden stairs up to the rooms. Lodging was cheap, about $10/night. We joked that it would be cheaper to live here than pay rent for our studio apartment in Wheaton, Illinois.

For $1 more you could turn on the A/C for your room. We declined – the mountain air was lovely. In the room, windows opened up to the intricate rice terraces maintained by the Yao people for centuries. It truly felt like we had landed in a hidden paradise.

The next morning, we wandered the trails winding around the mountains and terraces, admiring the clever irrigation systems that used hollow bamboo poles to transport water at an incline across the fields. I bought steamed glutinous rice patties wrapped in fragrant leaves from a woman stationed at one fork in the path.

The website chinabackpacker.info mentioned there was another little village not far from Da Zhai, called Xiao Zhai (小寨). In Chinese, the first means “Big Village” while the second means “Little Village.” Big Village was pretty small – a scattering of houses and gardens along the path, a hotel, and a restaurant or two. We were curious to see what Little Village was like in comparison.

Exploring Xiao Zai

We found a guide – a young Yao woman – to take us to Xiao Zhai. It was a couple-hour hike down the valley and over the next ridge. Unlike Da Zhai, Xiao Zhai had no tourist presence. Except us. A little creek ran downhill next to a path, and house-barns dotted either side. We took leave of our guide and walked uphill. In the midday sun, few people were out and about.

At the top of the trail a little waterfall spilled out over rocks and became the creek that ran through town. We sat on an outcropping and pulled out The Giver by Lois Lowry. (At this stage in life, with no children, we had the luxury of reading books out loud to each other).

After a while, we got hungry. We wandered back downhill and I knocked on a door. A short, squat woman with the traditional Yao woman’s hairstyle (wrapped like a crown around the head) opened, and I asked if there was anywhere in town to buy food. “No, but I can cook lunch for you,” she replied. We agreed, and stepped into her house.

Inside, a few walls partitioned off sleeping spaces along the side, as well as a bathroom, but everything else was open. Stools were scattered for seating around a low table. I noted sacks of what appeared to be corn and rice harvests.

In the kitchen, our host, whose family name was Pan, sat on a stool and chopped garlic on a wooden block. She had started a fire under a little metal stove with a wok on top. In Yao country, as we were learning, food options were limited: locally-grown vegetables, rice, and preserved pork. There were no grocery stores, except a small convenient store window attached to someone’s house where you could buy cigarettes and ice cream bars at .5 yuan each. Transporting food from bigger towns was time-consuming and expensive – you had to make the hours-long trip yourself.

We chatted with our host as she cooked and gratefully ate her homecooked food. As we were paying her and getting ready to leave, she asked if we wanted to stay for longer – she had a spare room upstairs. “That would be great!” we said. We had to return to Da Zhai that night as we already paid for the room, but the next day we would return to stay a couple nights in her house.

As promised, the next day we lugged our backpacks across wooden bridges and terraced hills (this time without an old woman pestering to carry them). We found Mrs. Pan’s home up near the waterfall and she showed us to an upstairs room. Chinese pop star posters lined the walls and a defunct computer and DVD player served as the end table. Here we were, spending 48 hours in a town with nary an inkling of tourist services. We were eating and staying with a local family and – with nothing much to do besides wander around and talk to folks – getting a real taste of village life.

Taking in Village Life

That night we had dinner at the little table the Pan family and some other villagers. Someone had made the tedious trip to the bigger city for more-than-local foods and procured fish, fresh pork, and ox skin. Ox skin was, apparently, a delicacy for special occasions. I struggled to chew and swallow the bristly chunks and wished they hadn’t taken the trouble.

The men had a curious custom of not eating rice with their meal until they had thoroughly drunken themselves on homemade sweet potato wine – rice would dilute the alcohol’s intended effects. I pitied Matt, who was expected to join the men in the rounds of 干杯 – going bottoms up with the shot glasses. He also gamely accepted the cigarette offered to him by an older man.

A younger man – Bian Neng – also joined us for dinner. He was home from working in Guangzhou. City life was hard, but village life was boring, he said. With each round of sweet potato wine, he became more garrulous. “I will start a business and ship my hometown wine around the country!” he declared. We also learned that roads and running water had just reached Xiao Zhai last year. The talk continued, and eventually we excused ourselves. Matt tripped up the stairs to the room, woozy from being a dutiful guest and imbibing all that was offered.

Not long after, we heard more voices – men’s voices – talking vehemently downstairs. Apparently, our host’s husband was something akin to a village mayor and this was the equivalent of a town hall. We shyly observed the goings-on from the stair landing, but – unable to make heads or tails of what was being so intensely discussed – we retired back to bed.

The next day Bian Neng took us hiking through the mist and to a breathtaking view of the terraces below. The trail was muddy and steep and I slid on my bottom all the way down and stood up again on jelly-legs.

After a midday rest, as we were standing out on the balcony watching a woman across the way brush her long black hair and arrange it into a lovely hair-crown, we heard a lute playing, some voices wailing, and a strange shrieking. The commotion came over the crest of the mountain and down the trail. It was a funeral procession. Some people carried sacks of rice. In the middle, men held the ends of two bamboo poles bound together. On the poles an enormous live pig was bound belly up and wriggling. That was the shrieking noise.

Later we walked over to the convenience store to spend 8 cents each on an ice cream bar. The village kids had the same idea. As they licked their bars, they crowded under what seemed to be the only TV in town to watch a show.

The morning after our second night staying at Mrs. Pan’s house, we paid her 200 yuan and thanked her profusely for her hospitality. Then we hopped on a bus and took the newly opened road from Xiao Zhai back to the city.

The Future of Xiao Zhai?

I imagine that our payment to the Pan family – about $30 USD and measly for us – was significant in proportion to what they earned annually selling their rice, corn, and salt pork. Tourism had already come to Da Zhai, just a jaunt across the fields. Now we tourists had arrived at Xiao Zhai and showed them the money-making potential in switching from purely farming to some in-between blend of both. With a newly-built road and running water, it seemed that the village was poised at the intersection between one way of life and another. Whether it was downhill or uphill after that transition, I still wonder.

Before the road was built, Xiao Zhai was relatively secluded from the bustling outside world. The village seemed peaceful and intimate when we were there. However, rice farming can only get you so far in life. As Bian Neng and his peers were showing, youth wanted more than the farming life, especially after seeing images of what that life could be on the one TV screen in town.

But when the young people leave, will they return? What will they return to? What new technologies and lifestyles will they bring back? Can a society built around the rhythms of sowing and harvest maintain a tight-knit community with an influx of outsiders eager to spend some money and have a good time?

Xiao Zhai was probably our most intimate experience of Chinese village life on our honeymoon. The next stop we made was to a Dong ethnic minority village. It was gorgeous too, but heavily catered to tourists. As we got off the bus we were diverted to seats around a stage where women and men performed traditional dances and then came around afterward holding out a tray serving tea and collecting tips.

Many restaurants in town served food that westerners would like, including “Frebch toast with Renut Sauce [sic].” (Matt took the bait, excitedly anticipating what he thought would be French toast and getting, disappointingly, a plate of dry toast with peanut butter). Compared to Xiao Zhai, this Dong village was like the Disneyworld Epcot version of a Chinese village. We didn’t converse with local people. Or, when we did, they expected our money.

To be fair, we paid Mrs. Pan too. But the exchange felt less extractive (on both ends) and more based in goodwill. In Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-term Travel, Rolf Potts described that this is the difference between tourist versus non-tourist areas. In tourist areas, because of the sheer number of people coming through, interactions will necessarily be more transactional and impersonal. Locals offering tourist services cannot be expected to share their life story with every inquiring traveler who comes through. In non-tourist areas, locals who show interest in you will be doing so more out of curiosity and desire for friendship than expecting to make a buck.

How much will Mrs. Pan’s village change as they welcome more tourists? Is it possible for a village to become a tourist destination without turning into a simulacrum of itself? Simulacrum is an academic word meaning that the real thing is packaged for consumption until it becomes a facsimile of the original – visually similar on the surface, but lacking substance – like the Epcot world villages.

Yet the flip side of simulacrum is the assumption that there is such a thing as “the real thing.” Are villagers “less authentic” when they wear t-shirts and Nike shoes instead of traditional garb? Or is that just what tourists want to see? Communities are constantly adapting, changing, and making the most of opportunities that come their way. If we go out in search of “authentic village life,” it’s worth examining whether our expectations are based in reality or on some Platonic ideal that comes from colonial images of “noble savages”. Most people in all parts of the globe want economic opportunity, life choices, and the amenities of modern life.

Each time we as tourists seek out “authentic untouched villages” and write home about the experience, we are by nature standing at the beginning of a trickle, possibly a flood, of tourists who will no doubt change what that village’s life even looks like. In this age of expanding global tourism, there are fewer and fewer of these kinds of places to be “discovered.” Perhaps it is enough to be welcomed in a place and spend our money, allowing villagers to decide for themselves what they want to share with us from the gems of their everyday existence.