Kids Grow Up So Fast. I’m Not Sure I’m Ready…

Dream

At five thirty in the morning, I woke up from a dream sobbing. Even two hours later, the effect hadn’t worn off. While walking to the coffee shop after my train commute, I had to gather myself. Tears were threatening to escape their prison. I couldn’t get caught crying at work. I wondered if I should take the day off. Was this a nervous breakdown? A midlife crisis?

As is typical of dreams, the content was weird and seemed to the waking mind inadequate to explain the strong emotions it provoked. In it, I catch my oldest son, Oliver, sitting cross-legged in the middle of the street in front of our house. (Despite the familiar setting, our front yard is bedecked with jungle foliage and there is a party of strangers milling about the kitchen around a leaking iced tea container. You know, the usual dream stuff).

I yell at him a bit too harshly, “Get the [expletive] out of the street!” After resisting he reluctantly mopes inside. I try to de-escalate my exasperation and reason with him that I’m just trying to keep him safe. His face is turned away from me, blank with a hint of derision. He wants nothing to do with me or my parental concern.

Passports

Earlier in the day, I saw that same look and thought I caught a glimpse of him as a teenager. He is eight.

It was late Sunday afternoon, I had just awoken from a nap and caught a second wind. I had the urge to check something off our long-term travel list. Passports, perfect!

“Get in the car, we’re going to get your passport photos,” I told Oliver and Finley (my five year old).

“I don’t want to go,” Oliver coolly stated.

“That’s fine. I guess if you’re fine with opening the door for our AirBnB guests and sleeping in the mudroom while the rest of us travel the world, you don’t have to go.” This was the tried and true scare tactic. I topped off the performance by walking away and putting on my shoes.

He called my bluff. “That’s fine. I’ll just stay home then. I don’t want to go.”

I resorted to my no-nonsense authoritative dad voice. “Get in the car. We need to get this done. It’s not an option.”

His expression was part contempt and part apathy. I wondered if this was what I had to look forward to once he hit adolescence. That is the facial expression that was indelibly captured on his passport photo.

It’s that face and that attitude that wormed it’s way into my subconscious and spawned my crisis dream.

Stages

A parent always loves their children. But that love takes on different shades and hues at different stages of life.

Babies don’t love you, they need you. And that’s something, I suppose. But they don’t love you in the way adults conceive of love. Nevertheless, you adore them. It’s a blissful martyrdom thanks to the oxytocin.

As they grow into toddlers—then little children—they enter what feels like a golden age. They don’t just need you, they want to be with you. They revere you, laugh at your jokes, laugh at your every belch and fart. They want to do what you do, and be just like you and you can’t help being flattered.

They sprout a personality all their own. Your love, likewise, fits itself to that new personality like a complimentary puzzle piece. Finally, all that lost sleep and rote servitude (a.k.a. childcare) find their reward.

It’s a satisfying love. It’s a love that never grows old. You might even mistake yourself for the best parent ever, because how else could you deserve this?

But then comes the transition to adulthood. They become… teenagers.

Being a dad hero used to be so easy.

Risk and Regret

I was once a teenager, now I’m five years away from being the parent of one. In ten years I’ll be the parent of three! With that in mind, I’ve been pondering the reasons why parents and teenagers so often cross wires.

I think I may have an idea of why (besides hormones). I believe it comes down to a difference in priorities.

Parents don’t want their kids to suffer. While that sounds selfless, the motives for this are not so clear. After all, parents suffer with their children, sometimes even more so.

Parents feel their children’s frustration and shame. But regret may take the trophy for things that give a parent heartburn. There is nothing more wrenching than the loss you could have prevented. There’s nothing like wishing beyond hope that you could just go back and change that one thing.

And as an adult you’ve seen a lot of regrettable things happen. Life altering (or ending) accidents. Co-workers lose their homes to poor financial decisions or just bad luck. Friends get into unhealthy or abusive relationships. You miss opportunities and only realize it when it’s too late.

Over time all that firsthand and secondhand experience of loss chips away at your younger self’s feeling of invincibility until you realize just how vulnerable you always were. And, more to the point, how vulnerable your child is.

Now add an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex to the mix and you have a young person blithely taking risks without appreciating what’s at play. And that pretty much sums up my life sentence with three boys.

It doesn’t seem fair. Why should a parent’s heart be in the hands of their offspring? If you lend me money, don’t you get a say in how I spend it? If we co-own a business, don’t we both get a vote on the big decisions? Both parent and child have skin in the game, but eventually only one gets to call all the shots.

But there is a second injustice. Does the child deserve to carry the double burden of their parents’ anxiety on top of their own? Is it the child’s responsibility to put their parents at ease when they already have the momentous task of finding their place in the world?

Different Priorities

I believe much of the friction between the younger and the older generations come down to priorities.

A parent’s main objectives for their child are that they:

- Outlive you.

- Avoid regret (and every other painful experience).

- Succeed (mostly for their happiness, with the side benefit of you looking like a first rate parent).

But it wasn’t that long ago that I was a teenager myself (at least that’s what I tell myself). And looking back, I can tell you I had a much different set of priorities.

What I really yearned for was to establish my identity and where I stood among my peers. For someone coming of age, those questions are the most pressing. What are my values? Do people like me? Who am I?

My first purchase as a freshman in college was an electric guitar because I thought maybe I was meant to be a rock star. An officer once clocked me driving one hundred miles per hour; I was trying on a bad boy persona (didn’t quite fit). I voted for Bush in 2004 because I wanted to stay true to the politics of my parents. I voted for Obama in 2008 because I had ideas of my own, separate from my parents.

A young person’s place in this world is uncertain and precarious. They have no laurels to rest on. Life is nothing but open doors and there is no prior investment in any of them. What’s the point of playing it safe to preserve something that one doesn’t have? Taking risks and trying on various personas is the best way to find out who you are and where you want to go.

So while the parent takes for granted that the child will have a satisfying and long life (“if only she listens to me and doesn’t ruin it!”), the child takes for granted that they can recover from any mistake (“if only my parents would get out of the way and let me figure it out on my own!”).

In the end, I think the kid is right (he says with a cringe).

Fear

It would seem I’m still years away from having to sweat all this out. My eldest son is eight. Five years is still some distance from the worries of today.

But he is precocious in some ways, and I can already see hints of what’s to come. The fault lines in our relationship are visible if you know where to look. They appear innocuous and insignificant, but they threaten a loud rupture. It’s enough to keep me up in the wee hours of the night.

It also doesn’t help that my own transition to adulthood was a fraught time between me and my parents. Even decades later, the relationship feels scarred and tenuous. I can’t help but feel hopeless in the face of this inevitable generational cycle.

But fear of the future is no guiding light. So what is a terrified parent to do?

A Prepared Mind, An Mindful Present

One thing I can do is gird myself for change. To welcome change as a part of life

When the boys were younger, I would discover clever ways to get them to stop crying, or do some chore. Every time that happened I thought I had hacked parenting. But just like computer hacks, people get wise and figure out how to undermine it, and you lose your edge. I may have to accept that as my boys get older, my attempts to exert authority and control will only become more futile as they set their own course.

I also need to keep an open and observant mind when our boys reveal new facets of themselves as time goes on. The labels I use to describe them today will likely need updating from time to time. Their personhood may change in ways that defy a tidy narrative. That puzzle piece that represents my love for them will need to be flexible enough to fit their ever-developing identity. I don’t want to get stuck just loving who they were at age five.

To ease my fears, I try to put my faith in love’s ability to repair the inevitable ruptures.

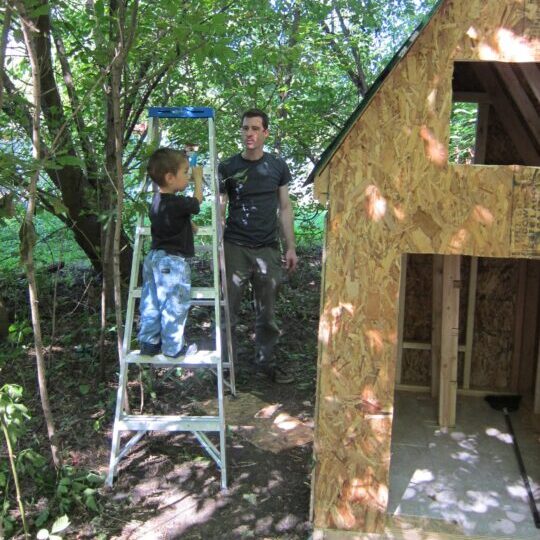

For now, I’m determined to enjoy this stage of our young family while it lasts. Taking a gap year (or two) is our way of doing this. Of course, that is not the only way to do it, and it is certainly not common. But the key is to make the present moment count. To be mindful that they way it is now will not last forever. I want to spend these “golden years” letting my children know I treasure my time with them.

When I woke up from my dream, I couldn’t fall back asleep. I laid awake terrified about what I was about to lose. I wondered if I had already lost something I couldn’t get back.

But when seven o’clock rolled around, Oliver burst into my room and flopped over the footboard onto my bed, like a high jumper. He came to see me before I left for work.

“Are you going to the office or working from home?” he asked, just like ever other week day.

At least this hadn’t changed yet. It filled me with relief. I still had my eight-year-old boy.